Inviolability of right to life, integrity of person

AS of December 31, 2024 (covering a period from January to December), death penalty abolitionist for all crimes were 113, abolitionist for ordinary crimes only were 9, abolitionist in practice were 23, total abolitionist in law or practice were 145, and retentionist were 54 countries worldwide (Amnesty International Global Report 2025: Death Sentences and Executions 2024).

These figures show for a significant number of jurisdictions the death penalty is no longer seen as an effective deterrent to crime and does not reduce crime rates either as thought before.

Tanzania is among abolitionist countries in practice, meaning that no person sentenced to death by hanging as provided for in section 2(1) of the Penal Code (R.E. 2022) has been executed since 1995 to date (for at least 29 years).

According to Tanzania Human Rights Report 2025: The Resurgence of Unknown Assailants published by Legal and Human rights Centre (LHRC), in 2024, 10 death sentences were imposed by the High Court of Tanzania in different regions across the country, including Tabora, Ruvuma, Shinyanga, and Dar es Salaam, and 9 out 10 convicts were men and one woman.

There were also over 700 death row inmates in Tanzanian prisons. However, Amnesty International Global Report 2025 figures show death sentences recorded by the end of 2024 in the country were at least 12, and people known to be under the sentence of death were at least 703.

Since human life is an inherent and inviolable right to all people, it is crucial to respect and protect it because once it is lost it cannot be reversed, and logically if one person’s life is not respected, and protected, even many lives will not be respected and protected in the real sense. A person cannot claim to be committed to respecting and protecting many people if he or she cannot commit himself or herself to respecting, and protecting one person. The value of human life does not lie in numbers, but in human worth, dignity.

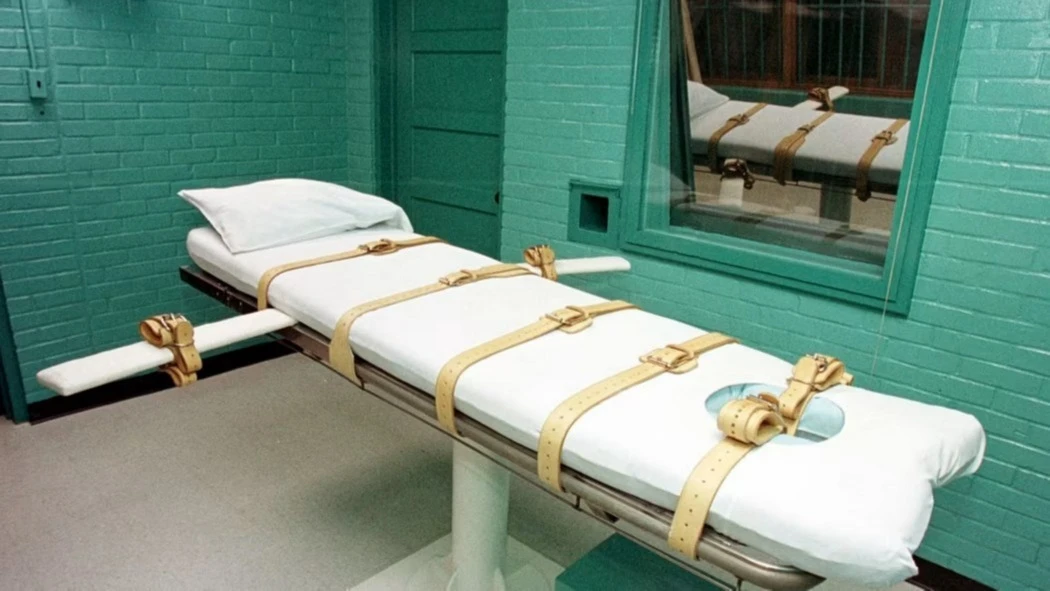

The more human life is respected and protected, the more it is valued and enjoyed. Death penalty negates the concept of the inviolability of the right to life and the integrity of a person.

Article 14 of the Constitution of the United Republic of Tanzania, 1977 (as amended until 2005) provides for the right to life. It states that “Every person has the right to live and to the protection of his life by society in accordance with the law.” A clause “in accordance with the law” qualifies the right to life (making it not absolute), while it is considered a non-derogative right. So, by virtue of section 26(1) of the Penal Code (Chapter 16) (R.E. 2022), the right to life can be derogated.

This means that a person shall legally be condemned to death by hanging if he or she commits certain grave offences such as murder (contrary to section 196, or treason (contrary to section 39) of the Penal Code.

The wording of Article 14 is different from constitutions whose Bill of Rights is entrenched. One of those constitutions is that of the Republic of Namibia. Article 6 of the Constitution of the Republic of Namibia, 1990 (as amended until 2014) provides for the protection of life.

Sub-Article (1) states that: “The right to life shall be respected and protected. No law may prescribe death as a competent sentence. No Court or Tribunal shall have the power to impose a sentence of death upon any person. No executions shall take place in Namibia.”

Article 131 provides the entrenchment of fundamental rights and freedoms (stipulated in Chapter 3). It states that “No repeal or amendment of any of the provisions of Chapter 3 hereof, in so far as such repeal or amendment diminishes or detracts from the fundamental rights and freedoms contained and defined in that Chapter, shall be permissible under this Constitution, and no such purported repeal or amendment shall be valid or have any force or effect.”

Article 11 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (as amended until 2012) too provides for the right to life. This right is unqualified (has no clause which qualifies it). It states that “Everyone has the right to life.” So, as the article is worded it cannot be abrogated either.

It is not so in Tanzania, where a person who commits the offence of murder or treason after it is proved in court that he or she committed it he or she shall be convicted of murder or treason, and be sentenced to suffer death by hanging as provided for in section 26(1) of the Penal Code (Chapter 16) (R.E. 2022).

I would like to conclude this column with the decision of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (AfCHPR) in one murder case. In the matter of Ally Rajabu and Others v United Republic of Tanzania (Application No 007/2015a), the applicants who are Tanzanian nationals were sentenced to death by hanging for murder contrary to section 196 of the Penal Code (Chapter 16) and were imprisoned at Arusha Central Prison.

In its judgement, the AfCHPR found that the Respondent State (Tanzania) violated Article 4 of the Charter by providing for the mandatory imposition of the death penalty in its penal law. It also found a consequential violation of Article 5 of the Charter in respect of the execution of the sentence by hanging.

Consequently, the Court ordered the Respondent State to take all necessary measures so that the applicants were sentenced through a process that did not allow a mandatory imposition of the death penalty, while upholding the full discretion of the judicial officer.

Basing on its earlier order on the sentencing of the applicants the AfCHPR said the case should be heard afresh, which amounted to a systemic pronouncement since it would inevitably require a change in the law. Therefore, it made the consequential order so that the Respondent State undertook all necessary measures to repeal from its Penal Code the provision for the mandatory imposition of the death sentence. In this way, non-execution of convicts sentenced to death by hanging (commutation) is consistent with the respect and protection of the right to life and integrity of a person.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED