E-Learning in Africa: Expanding access and opportunities across the continent

DAR ES SALAAM was buzzing with intellectual energy and continental pride as more than 20 education ministers and high-level representatives from across Africa gathered for the 18th eLearning Africa Annual Conference and Exhibition.

Held from May 7 to 9, 2025, at the Julius Nyerere International Convention Centre, the conference highlighted not just the rising influence of digital learning on the continent, but a quiet revolution already underway.

"Digital education is not a trend," said Tanzania’s Minister of Education, Science and Technology, Adolf Mkenda, during the opening ceremony. "It’s a critical response to the challenges of our time."

The conference was more than a showcase of tech tools and training modules. It was a convergence of ideas, passion, and urgency. It united policymakers, innovators, scholars, and funders—all focused on one mission: harnessing technology to empower learners everywhere, especially those who’ve historically been left behind.

Behind much of the momentum in Tanzania stood a woman who’s become synonymous with distance learning in East Africa: Professor Cornelia Muganda. Now retired, Prof. Muganda remains a force. As one of the key architects of the Open University of Tanzania’s early frameworks, she championed not just access to education, but the dignity that comes with it.

“We didn’t push for distance education because it was fashionable,” Muganda reflected in one of her think pieces. “We pushed because it was necessary. Girls in villages, single mothers, working adults—they all deserved a second chance”.

Muganda’s legacy is felt in every tablet distributed in a rural district, in every online bootcamp accessed from a solar-powered classroom, in every Tanzanian teacher trained in digital pedagogy. Her work, decades ahead of its time, helped lay the groundwork for what the country is now attempting to scale.

Minister Mkenda acknowledged this, outlining how the government is moving from isolated pilot projects to national strategies. “We’ve started distributing tablets to teachers, enhancing connectivity in schools, and building content that speaks to our needs,” he said. “Through the Tanzania Institute of Education, we’re working with NGOs and global partners to digitize our curriculum, not just replicate what’s printed in books.”

He also spoke of the Samia Scholarship initiative, which supports between 50 and 100 students each year to study tech-intensive fields abroad, particularly artificial intelligence. “These are not just scholarships,” he added. “They’re investments in the minds that will build our digital future.”

This future feels personal to many who attended the conference. The corridors echoed with voices sharing lived experiences—stories of resilience, adaptation, and determination.

For some, digital learning meant finally being able to balance education with family duties. For others, it was the opportunity to gain international credentials without the high cost of relocation.

Johannes Bontlogile, a communications strategist from Botswana, noted the emotional undertones of the gathering. “You felt people weren’t just there to learn. They were there because something in this mission had touched their lives or communities.”

There was also the unspoken awareness of what still holds the continent back. Infrastructure gaps, electricity shortages, and rigid bureaucratic processes were discussed candidly, but not as excuses—as realities to overcome.

Many speakers pointed out the pressing need for more flexible and country-specific copyright policies to enable broader access to digital learning materials. A South African delegate noted, "In some places, students have to break the law to learn. That’s unacceptable."

The stakes are high. As distance and digital learning grow, so do questions of quality assurance. A recently presented Tanzanian study highlighted that while several public institutions offer Open and Distance Learning (ODL) programs, there is still a lack of centralized oversight. The absence of a national ODL policy means institutions operate in silos, each defining their standards.

“We’ve seen success,” said Dr. Emmanuel Kigadye from the Open University of Tanzania, “but without a harmonized framework, we risk fragmentation. That’s why this conference matters. It brings us together to align and strategize.”

The alignment was visible in every breakout session. From using artificial intelligence to support personalized learning, to blending radio with digital tools to reach the remotest corners, innovation was not abstract. It was grounded, gritty, and focused on solving real problems.

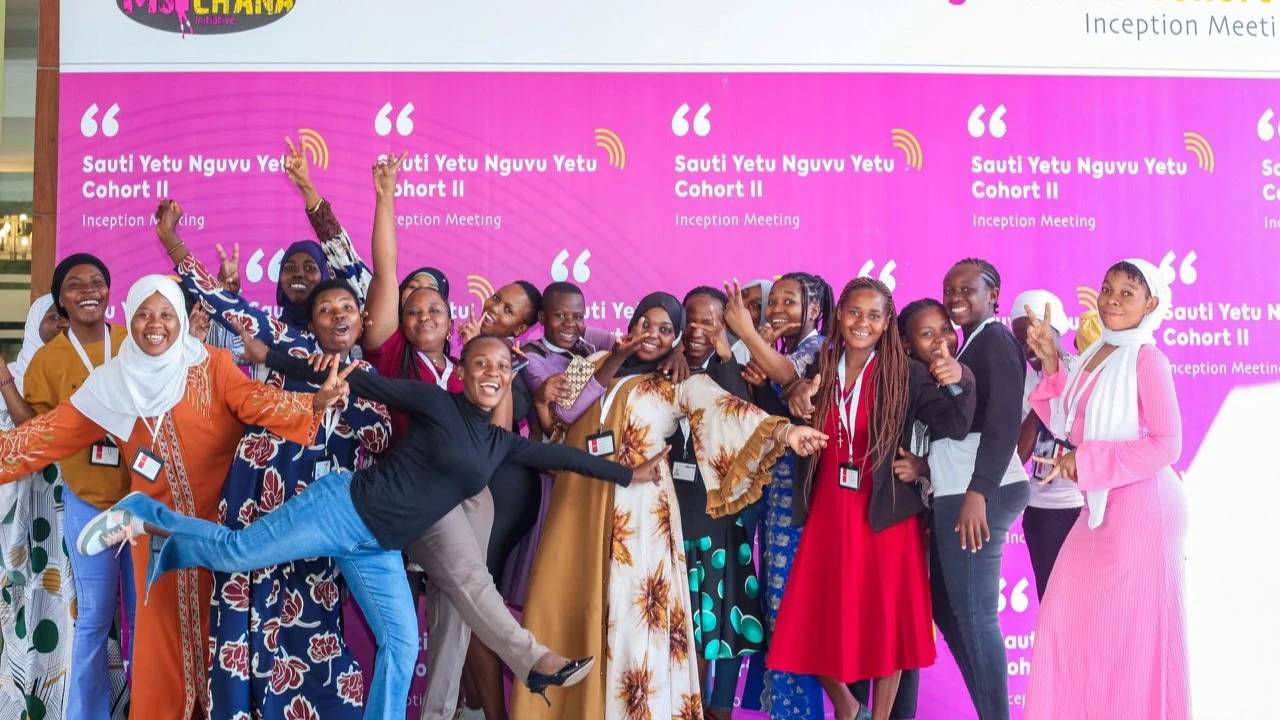

Some of the most moving moments came not from keynote addresses, but from students. One young woman from Lesotho shared how, thanks to DeAfrica’s scholarship and an internet connection, she was now tutoring other girls in her village. “They call me ‘Madam Teacher,’” she laughed. “And sometimes I can’t believe it myself.”

These personal triumphs formed the emotional backbone of the event, reminding everyone that this isn’t just about platforms and policies. It’s about people—about access, identity, and agency.

Sidiki Traore, Founder of Distance Education for Africa, who was also in attendance, shared his reflections during a panel discussion. “When we started, people asked if Africans would take to online learning,” he said. “Today, the question is: how fast can we scale it?”

His organization, DeAfrica, is currently conducting a five-country tour showcasing the success of its scholarship cohorts and preparing for a grand graduation in Nairobi this June. But even with his growing influence, Traore credited the work of unsung heroes like Muganda. “We’re all standing on her shoulders,” he said simply.

In every country DeAfrica visits, the story is the same—of lives changed, barriers broken, and horizons expanded. In Eswatini, a young mother who once worked in a market now tutors others in coding after completing her course online. In Lesotho, rural health workers are earning certifications that were once out of reach, and using them to educate communities on public health and nutrition. And in Kenya, some scholarship recipients have gone from refugee camps to tech internships, their journeys driven by nothing more than access and ambition.

What sets DeAfrica apart isn’t just its reach but its deep understanding of local realities. The programs are designed not just for broadband-rich cities but for areas where a mobile phone may be the only link to the internet. Traore's team ensures learning content is offline-accessible, mobile-friendly, and tailored to local contexts, languages, and challenges.

Other countries have also carved notable paths in the e-learning space. Rwanda has woven digital literacy into its national curriculum, ensuring students learn both theory and tech from the ground up. South Africa, despite its inequities, continues to lead in platform innovation and university-led online programs. Ghana, with its burgeoning youth population, has fostered public-private partnerships that scale learning to thousands.

Back in Dar es Salaam, the momentum at the eLearning Africa conference was unmistakable. Over the three days, more than 20 ministers and hundreds of educators, tech developers, and investors exchanged strategies, data, and dreams. Conversations turned into commitments. Pilot programmes into national strategies. Partnerships once tentative now felt inevitable.

Though Prof. Muganda wasn’t at the conference, her impact was clear. Years of advocating for distance learning are finally taking shape—her ideas turning into real programs and policies across Africa. While she may be retired, her work continues to break down barriers and open doors for countless learners, quietly shaping the future she helped imagine.

With initiatives like the Samia Scholarship, regional alignment through conferences like eLearning Africa, and the tireless efforts of educators, technologists, and policymakers across the continent, digital education is no longer just a promise. It is happening—vividly, powerfully, and irreversibly. And for the countless students logging into lessons from kitchens, fields, refugee camps, and crowded cities, it means the world.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED