Malaria fight in Tanzania: Why some regions still suffer

EVERY two months, one of Eva Boniface’s three children falls ill with malaria, despite using a mosquito net. She is forced to spend extra money on medication and food when her children, aged nine, six, and four, get sick.

The resident of Ipuli, Tabora municipality, says that malaria remains a significant problem in her area due to insufficient community education on the proper use of treated mosquito nets, lack of proper drainage and high cost of malaria prevention and treatment.

“Even though malaria treatment is free for children, some medications, like anti-nausea drugs, must be purchased. Additionally, a sick child often becomes picky with food, so I have to go beyond my budget to satisfy them,” she said.

Eva added that sometimes the hospital runs out of malaria medication, forcing her to buy it from pharmacies since she cannot wait for the hospital's stock to be replenished.

Eva’s story is one of many in Tanzania, where malaria remains a persistent threat in some regions despite significant progress in reducing infections nationally.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), malaria prevalence declined from 14 percent in 2015 to 8.1 percent in 2022. However, the disease continues to affect some regions significantly and Tanzania is still among four countries—alongside Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Niger—that accounted for just over half (52 percent) of all global malaria deaths in 2021.

Furthermore, malaria remains a leading cause of death for children, with 260,000 fatalities annually in sub-Saharan Africa.

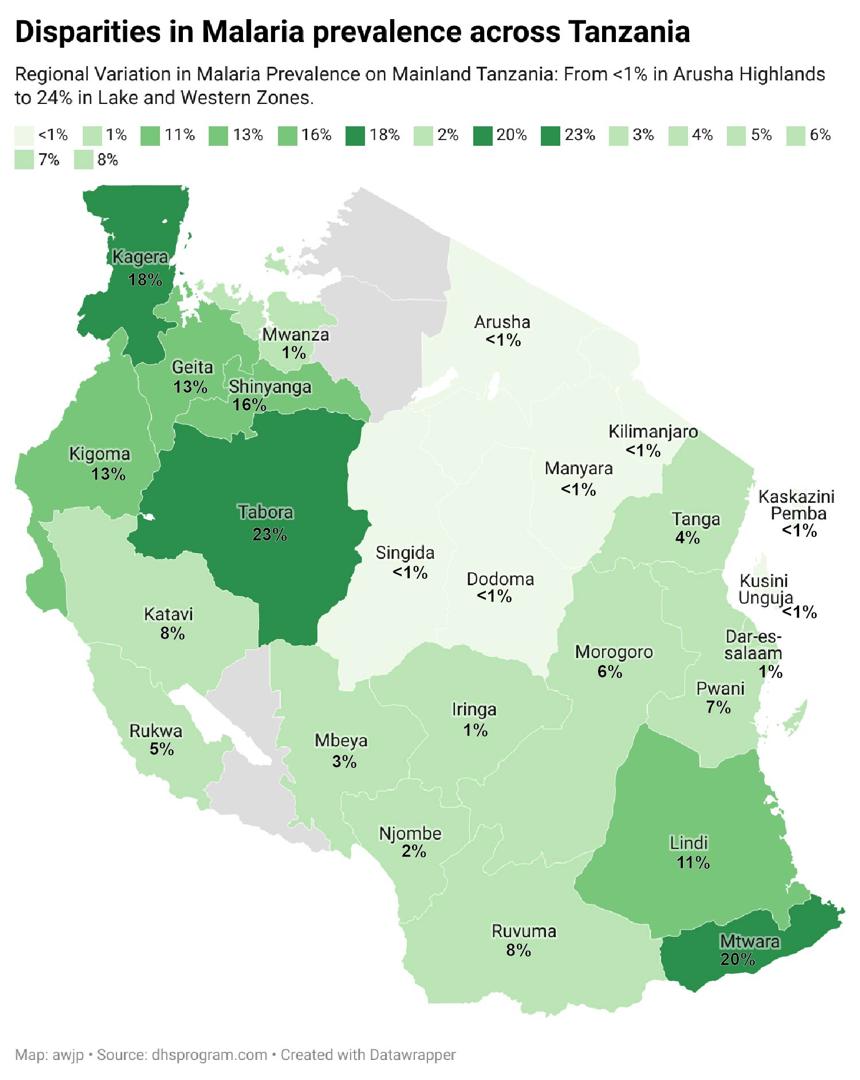

In Tanzania, infections vary widely by region, ranging from 1 percent in the highlands of Arusha to 15 percent in the Southern Zone and up to 23 percent in the Lake and Western zones. According to the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2022, regions such as Tabora, Kagera, and Katavi still face high infection rates, posing significant challenges to the goal of eliminating malaria by 2030.

Environmental factors

Geographical factors and climate change have exacerbated mosquito breeding sites in these regions, making malaria control efforts more difficult.

For instance, in Igunga District, Tabora Region, abandoned water ponds have become mosquito breeding grounds, contributing to the high malaria rates.

Additionally, insufficient funding from many local councils for malaria prevention and treatment, weak enforcement of public health regulations, and a lack of community awareness on the proper use of treated mosquito nets hinder control efforts.

Josephat Kawambwa, a 36-year-old resident of Kashenge village in Bukoba District, Kagera Region, knows this all too well. He first fell ill last March, and after diagnosis and treatment with a four-day dose of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ALU), he fell sick again just two weeks later.

“I had headaches, vomiting, and dizziness. I went to the district hospital, where I was found to have three malaria parasites. Since I had already taken medication, they prescribed injections. But three weeks after completing the dose, the illness returned,” he narrated.

This time, he contacted his brother in Dar es Salaam, who sent him money for travel to receive treatment at Temeke District Hospital, in Dar es Salaam Region where he underwent a full blood count, urine analysis, and malaria test.

Results showed he had two malaria parasites. The doctor prescribed the same ALU medication as before. After completing the dose, he returned to the hospital for testing and was declared malaria-free.

Kawambwa realised that the environment and lack of proper malaria prevention measures were the key factors in his recurrent bouts of malaria.

“I had a mosquito net given for free by the district council, but I used it to make a chicken coop because it didn’t fit my bed. In Bukoba, I didn’t use a mosquito net or spray insecticide, so mosquitoes bit me, leaving marks. But here at my brother’s home in Dar es Salaam, I sleep under a proper mosquito net, and the house is regularly sprayed, so there are no mosquitoes inside,” he said.

Kawambwa’s experience underscores the need for better-fitting mosquito nets for all bed sizes, improved public education, and community-driven malaria control measures in other parts of Tanzania with high rates of malaria infection, just like in Dar es Salaam.

Mariam Salehe, a resident of Ilala, Dar es Salaam, acknowledged the government’s efforts to combat malaria in the city. These include eradicating mosquito breeding grounds, educating people on prevention and distributing mosquito nets annually to children through schools.

“For the past three years, my family, including my two children and husband, has not suffered from malaria. It’s not that there are no mosquitoes, but we take precautions. Before heading out in the morning, we ensure we’ve sprayed insecticide, and when we return in the evening, the mosquitoes are already dead,” she said.

Government efforts

As a result of government efforts, malaria infection rates fell from a high of 50–60 percent in the 1990s to 8 percent in 2022, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Regions such as Dar es Salaam, Dodoma, Iringa, and Mwanza have achieved significant reductions, with infection rates as low as 1 percent.

Dr. Rashid Mfaume, Director of Health Services, Social Welfare, and Nutrition at the President’s Office–Regional Administration and Local Government (TAMISEMI), says special budgets are allocated for purchasing insecticides and implementing control measures in high-prevalence regions like Katavi, Tabora, and Kagera.

Progress and future plans

For the 2024/2025 fiscal year, the government allocated TZS 10 billion for the purchase of larvicides and TZS 1 billion for spraying equipment. Efforts also include distributing free mosquito nets to children and pregnant women, environmental sanitation campaigns, and the use of biological larvicides.

Prevention efforts

Dr. Lazaro notes that while prevention and treatment strategies have contributed to progress, continued efforts, including vaccination, are crucial. He mentioned that the government is strengthening malaria prevention and treatment efforts by strengthening local industries such as Tanzania Biotech Products Limited in the Coast Region, which produces larvicides to combat mosquito larvae that spread malaria. For the 2024/2025 fiscal year, 10bn/- has been allocated for purchasing larvicide from the factory in Kibaha. Additionally, 1bn/- has been allocated to buy spraying pumps.

Dr. Lazaro stressed the importance of community education and proper diagnosis before treatment.

"The government also continues to provide free malaria treatment for patients and urges citizens to get tested before using medication. Not every fever is malaria, so we encourage people to test and ensure they complete their dosage to prevent drug resistance," he said.

While Tanzania has made significant progress, continued investment in prevention, public education, and new medical interventions will move the country closer to its goal of eliminating malaria by 2030.

This article was produced as part of the Aftershocks Data Fellowship (22-23) with support from the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with The ONE Campaign and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED