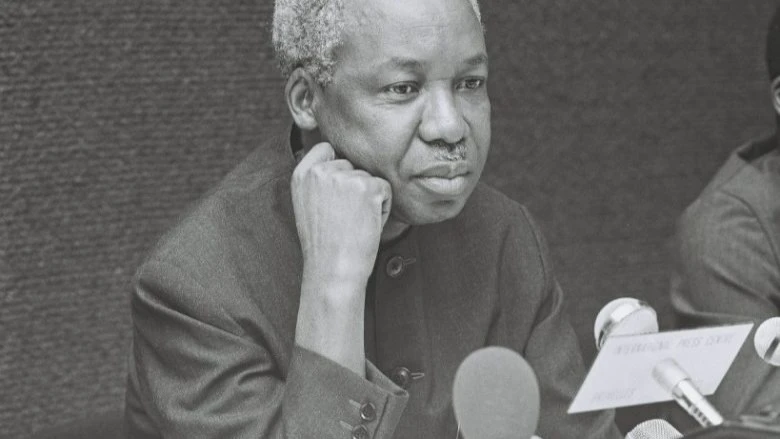

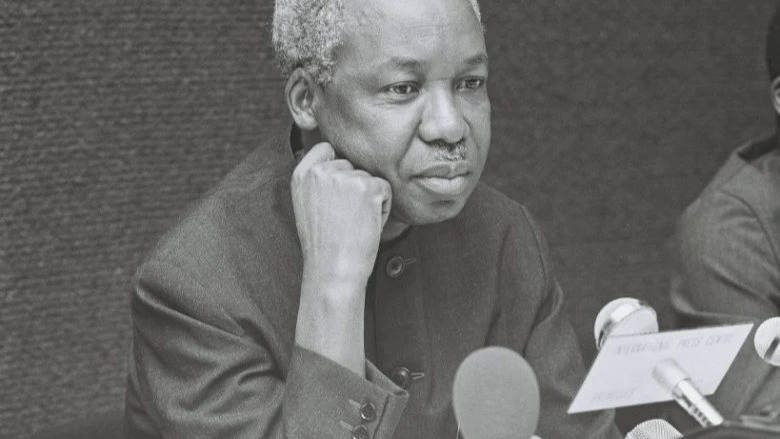

Mwalimu’s legacy and the African health mission

AS Tanzania marks Mwalimu Nyerere Day 2025, memories return of a leader whose style was defined by service, and moral conviction. For Nyerere, leadership meant walking alongside his people and Africa, lending his hand without pretense, and advancing collective upliftment over personal aggrandizement. It is only fitting therefore that in this era of looming health crises in Africa, we reflect on his ethos and unite through our regional leaders to mirror his servant leadership in shaping Africa's health future.

Fifty‑one years ago, in 1974, the East, Central and Southern Africa Health Community (ECSA‑HC) was established under the auspices of the Commonwealth Secretariat to harness collective strength across neighbouring states (then British Commonwealth) to tackle shared health burdens. Its founding objective, to promote cooperation and regional capacity in health, was simple yet profund. Mwalimu was one of the founding fathers of ECSA HC and his dream was such that no nation had to confront epidemic threats, resource scarcities, or policy deficits alone.

Over time, that aspiration took root. By 1980, member states formally took over ownership under a Convention signed by their health ministers, giving the organization a political and legal foundation. Today, ECSA‑HC encompasses nine full member states (Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Eswatini, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe) and offers technical support to over 16 other countries.

But while the vision was noble, the terrain has grown far more complex. Africa’s is now witnessing a health systemic strain characterised by several global vulnerabilities:

Underinvestment and funding shortfalls

Despite the critical role of health in societal stability, many African governments fall short of globally recommended thresholds. A recent Human Rights Watch analysis showed that, among African countries, many allocate well under 5 percent of their national budgets to health (for Tanzania, about 5.1 percent; for Zimbabwe, about 5.2 percent). Donor dependence remains the order of the day with many countries seeing more than 30–40 percent of their health sector budgets supported by external aid.

Import dependency and fragile supply chains

One of the starkest vulnerabilities in Africa’s health infrastructure is the overwhelming dependence on imports for medicines, diagnostics, vaccines and devices. Estimates indicate that 70 %–90 % of medical products consumed in Africa are imported. In pharmaceuticals, the continent produces only 25–30 percent of what is consumed locally, and less than 10 percent of medical supplies. For vaccines, Africa produces under 1 percent of vaccines used on the continent, making it painfully vulnerable to supply chain shocks.

In Tanzania and Ethiopia, comparative studies of locally produced vs imported medicines reveal nuanced dynamics. In Tanzania, local products were procured at lower relative cost than imports (median price ratio MPR 0.69 vs 1.34), but availability for local products was lower in private outlets, and procurement planning often favored imports. In Ethiopia, imported medicines were in many cases cheaper (median MPR 0.84) than local ones (1.20), though local availability was somewhat better in public outlets. Such variability underscores that local production is not a panacea. it must be backed by strong procurement, regulation, distribution, and quality systems.

The COVID‑19 pandemic exposed the fragility inherent in Africa’s overreliance on external supply chains. Export restrictions, global competition for raw materials, and logistical bottlenecks led to shortages of masks, personal protective equipment (PPE), oxygen, diagnostics, and vaccine access delays. Many countries found themselves unable to respond independently to surges, intensifying mortality and disruption.

Going forward, global health financing architecture is shifting: multilateral institutions, donor priorities, and development banks are pushing for greater local manufacturing, regional supply chains, and “health sovereignty” models. The African Union’s “New Public Health Order” emphasizes strategic autonomy in health, including investment in local production of medicines, diagnostics, and technology.

Given this shifting landscape, Africa cannot afford to remain a passive consumer. The motto “Buy Africa, Build Africa” must move from rhetoric to reality, especially for regional bodies like ECSA‑HC.

For this to be attained, we must adhere to Mwalimu Nyerere's Servant Leadership codes:

Pooled procurement and regional manufacturing hubs

ECSA‑HC member states should lead in creating pooled procurement platforms for medicines, diagnostics, and supplies. By aggregating demand across multiple countries, the region can negotiate better prices, assure predictable volumes, and incentivize local manufacturing.

Complementing this, regional manufacturing hubs should be developed in strategic locations (e.g. East Africa, Southern Africa) to produce APIs, fill‑finishing, diagnostics, and medical devices. Countries with nascent capacity e.g. Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania could host scale-up facilities. Such hubs would benefit from economies of scale, cross‑border standards, and favourable trade agreements under the African Continental Free Trade Area AfCFTA.

Harmonized regulation, quality and standards

Local manufacturing must be underpinned by strong regulatory systems. ECSA‑HC should coordinate efforts to strengthen national regulatory authorities toward WHO maturity levels, harmonize regulatory frameworks, and support the Africa Medicines Agency (AMA). This reduces duplication, lowers entry barriers, and enhances trust in locally made products.

Investment and incentives for local industry

Governments must adopt smart investment and procurement policies: tax incentives, subsidies, special economic zones (health clusters), and public–private partnerships targeted at pharmaceutical and diagnostics firms. UNCTAD argues that such enabling policies are critical to attract capital to local production. International finance institutions should be lobbied to prioritize investments in manufacturing for health in Africa.

Strengthening health systems and supply chains

Manufacturing alone is insufficient. Reliable raw materials availability, dependable distribution systems, cold chain logistics, inventory forecasting, digital supply tracking, maintenance capacity for devices are all essential. ECSA‑HC should support member states with technical assistance in raw materials availability, supply chain strengthening, digital procurement systems, and capacity building.

Regional health financing mechanisms

To reduce donor dependency, ECSA‑HC countries should explore regional health insurance schemes, solidarity funds, and cross‑border health levies. Resources mobilized domestically and regionally can be invested in essential health commodities and infrastructure.

Coordinated pandemic preparedness and stockpiles

ECSA‑HC must champion regional strategic reserves of critical supplies (e.g. PPE, oxygen, diagnostics) and support joint pandemic preparedness initiatives. A coordinated emergency operations center (EOC) and mutual aid protocols will allow rapid deployment across member states.

Leadership, governance, and servant-leadership approach

To actualize these joint ventures, Africa must adopt servant leadership styles. We need ministers who listen, empower, and align across borders. Just as Nyerere emphasized service above dominance, ECSA‑HC leadership must act as integrators, bridging ministries, the private sector, academia, and civil society to design region‑wide strategies.

On this Mwalimu Nyerere Day, as Tanzania and the region reflect on his life, let his example of humility and community service inspire African health leadership to do more than set policies. Let our leaders walk the corridors of clinics, understand the plight of rural nurses, and mobilize collective will to make medicines, diagnostics, and care affordable.

ECSA‑HC has served for half a century as a regional anchor. But today, amid shifting global health patterns and Africa’s growing demographic pressures, it must lead audacious transformations. Africa must move from mere passive importers to empowered producers. To attain this, Africa should desist from fragmented systems and move to unified regional platforms. Donor dependency to sustainable at all.

Africa must chart a new and urgent course of health sovereignty. Regional bodies like ECSA‑HC and it's member states, guided by Mwalimu Nyerere's servant leadership antics and anchored in his shared vision for an independent Africa, must lead the way.

Bryan Bwana is the Founding Trustee, Umoja Conservation Trust

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED