Well done Treasury Registrar, even with capital inflows snag

THAT a total of 900bn/- has been collected over an 11-month period from companies where the government holds shares, with expectation to reach 1trn/- by the end of this financial year is unquestionably good news, especially as it is a vast improvement from the previous financial year, by nearly a half of the previous year’s collections.

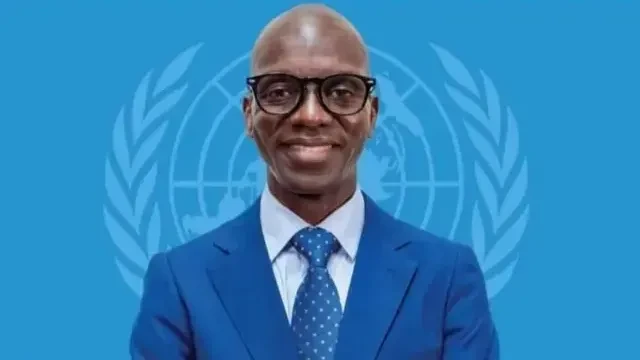

It speaks plenty in support of the current Treasury Registrar who has used much of the past year to profile a range of technical innovations to improve fiscal performance with parastatal organisations. There is clearly something to be shown for those efforts, with 300bn/- extra dividends.

At a media briefing the registrar said that there was a 40 percent increase in non-tax revenue collections from public and statutory corporations, along with minority interest entities. This introduction was being conducted ahead of dividend day scheduled for 10th June at the State House in Dar es Salaam, which for once makes parastatal agencies a significant budget contributor. Despite this progress, there are major parastatals that suck up large amounts of public funds and it is to these that reform push has usually faltered due to habit.

Interestingly this achievement has plenty to do with revenue from public institutions and companies where the government holds minority shares, rising from 633.3bn/- collected during the corresponding period for fiscal 2023/24.

There are other areas of fiscal uplift but this is the main component, which evidently suggests that this format ought to be the model on which government shares need to be held. When the government is in a minority, private sector methods dominate and thus there is efficiency, while the opposite also applies.

There was time, specifically early 1981, when founder President Julius Nyerere spoke strongly against pressure to privatise, from Bretton Woods institutions, such that the campaign, known as structural adjustment, collapsed as a strategic economic reform project.

It remained for loss making marginal parastatals like regional transport companies or district retail trade outfits which were habitually loss making. As part of a new understanding with the IMF and the World Bank in the early1990s two major firms were privatised, the beer and tobacco firms.

Another bit of trouble arose in the mid-1990s when the World Bank demanded the splitting and privatisation of the National Bank of Commerce as essential to strategic streamlining of financial sector services. It was done but it left a spur taste in the mouth, such that nothing of the sort was done later, with 51 by 49 percent share distribution failing for Air Tanzania, telecommunications and railways. So when the registrar says that this revenue growth arose from better oversight of dividends and adoption of digital information systems that is only partially true, as in the final analysis is the minority shares firms that pile cash.

It is unlikely that the office of the registrar has methods it can use, like an integrated planning and budgeting system with enterprise resource management or enhancing the government digital payments system to alter this cash flow structure. By the government’s own fiscal data, we lose plenty when we stick to statutory ownership of more than 300 commercial entities, whereas they can attract large amounts of capital if we seek strategic investors in all of them. The minority shares can be retained by the state, or placed on the stock exchange.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED