Blue economy: Zanzibar’s seaweed farmers demand fair prices

CREATING a conducive business environment for seaweed farmers can drive significant progress in youth employment, empower women, and enable Tanzania to fully benefit from the blue economy.

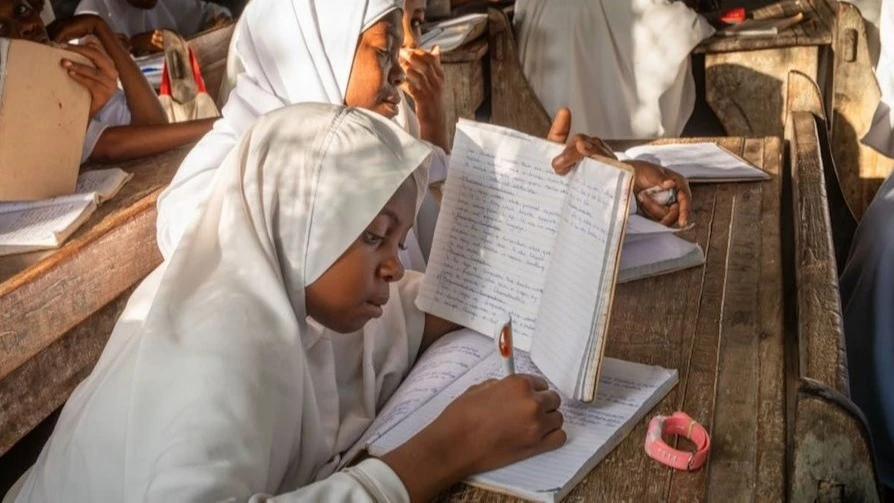

Seaweed cultivation in Zanzibar has emerged as a vital economic activity, particularly for women, providing employment, supporting livelihoods, and contributing to Tanzania’s growing blue economy.

Zanzibar is one of the world’s leading seaweed producers. The archipelago exports around thousand tonnes of seaweed annually to international markets, including Japan, the USA, Denmark, China, and Spain. The industry directly employs approximately 30,000 farmers, with 80 percent being women.

Seaweed farming is an environmentally friendly practice that requires no fertilizers or pesticides. It contributes to marine conservation while serving as a raw material for various industries, including cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and food production.

Women engaged in seaweed farming in Unguja Island, Zanzibar, are calling on the government to set an indicative price for Spinosum seaweed, raising it from 700/- to 3,000/- per kilogram. They believe this adjustment will enable them to better support their families, improve their livelihoods, and secure better housing.

Safia Makame, a 60-year-old seaweed farmer from Bweleo village, emphasized the need for government intervention. Despite their hard work and investment, the prices they receive remain extremely low.

Farmers are also requesting that the price of the Cottonii seaweed species be increased from 1,000/- to 2,000/- per kilogram.

“If the government supports this initiative, higher prices will attract more youth and women to seaweed farming, ultimately benefiting coastal communities and unlocking the full potential of the blue economy,” Makame stated.

Challenges pushing farmers away

Due to persistently low prices and the growing impact of climate change, some women have abandoned seaweed farming and turned to casual labour, vegetable farming, or small businesses to make ends meet.

“We produce a large quantity of seaweed, but there is no market, and prices remain low,” Makame explained, insisting the need for the government to provide boats, swimming training and drying facilities for better production.

Dr Flower Msuya, founder of the Zanzibar Seaweed Cluster Initiative (ZaSCI), highlighted that rising ocean temperatures and extreme sunlight have led to the rotting of nearly 70% of seaweed. Many farmers are now struggling to adapt to changing weather conditions.

With 80 villages cultivating seaweed in Unguja Island, the sector holds immense economic potential. Seaweed products are exported to markets in France, the USA, Denmark, China, Spain, and Chile.

However, climate change is forcing farmers to seek deeper waters for cultivation—a major challenge, as most women cannot swim or afford boats to reach these areas.

To help seaweed farmers sustain their livelihoods, Dr Msuya urged the government to provide modern fiber boats, swimming training, and improved drying facilities, such as large solar dryers.

Additionally, she emphasized the need for better access to affordable packaging materials, which remain scarce and expensive.

A recent study conducted in Zanzibar revealed that women seaweed farmers face increasing seawater temperatures (31–38°C), high postharvest losses, ice-ice disease, and epiphyte pests—factors that severely impact seaweed growth. Some farmers have resorted to storing seaweed seeds in deeper waters, waiting for the hot season to pass, while others struggle to access new seeds.

The challenges extend beyond climate change. Competition for marine resources is creating conflicts between seaweed farmers, the fishing industry, and the tourism sector.

Fishermen often invade seaweed farms, damaging crops and cutting ropes. Additionally, pollution and theft—especially of valuable sea cucumbers—pose further threats.

To address these issues, Dr Msuya recommended implementing marine spatial planning to designate specific areas for seaweed farming, tourism, and fishing.

Seaweed farming in Tanzania employs 30,000 farmers, 80 percent of whom are women. Despite their contributions, the current price of 700/- per kilogram is too low to transform their lives.

Pius Mwakalebela, manager at Mwani Zanzibar Co. Ltd, pointed out that in Europe, seaweed fetches up to 150 euros per kilogram. He warned that without government intervention, women will remain trapped in poverty despite years of hard work.

Zanzibar ranks third globally in seaweed exports shipping 75,000 tonnes annually to international markets. However, many men have abandoned the sector due to low prices, leaving women to bear the brunt of the industry's challenges.

Beyond its economic benefits, seaweed farming is an environmentally friendly practice that requires no fertilizers or pesticides. It can be used to produce food, fertilizers, and cosmetics. Seaweed is also rich in essential minerals, offering health benefits such as wrinkle reduction, weight loss, and thyroid support.

To fully realize the potential of seaweed farming, Mwani Zanzibar Co. Ltd has launched a value-addition project, producing seven types of soaps, scrubs, and seaweed butter for domestic and international markets.

For these women, fair pricing, government support, and better access to resources are critical steps toward a sustainable and prosperous blue economy.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED