Global depopulation amidst gains in average longevity

A United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) report titled “World Fertility 2024” shows a gradual decrease in global fertility. It says the global fertility rate in 2024 was 2.2 births per woman on average, down from about 5 in the 1960s, and 3.3 in 1990. It is projected to continue declining, reaching the replacement level of 2.1 in 2050, and falling further to 1.8 births per woman in 2100.

“Trends in fertility, together with trends in life expectancy and international migration, determine the speed and duration of population growth or decline as well as the direction and magnitude of changes in the population age distribution, including population ageing,” the report says.

Tanzania is among the countries with rapid population growth. While in 2022 it had 61.7 million people, its population is projected to reach 151.3 million people in 2050 (in 25 years). A report titled “The Fertility and Nuptiality Levels and Patterns in Tanzania” published by National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), and the Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS) (2025) shows the total fertility rate (TFR) in Tanzania is 4.6 children per woman. In Zanzibar, the fertility rate is 4.7 children per woman.

This translates into saying on average a Tanzanian woman is likely to give birth to 4.6 children, and a woman in Zanzibar is likely to give birth 4.7 children by the end of her reproductive age. The TFR level in Tanzania shows a decrease from 6.9 children per woman recorded in 1978 (equivalent to a reduction of 2.3 children per woman for the past 44 years).

According to the NBS and OCGS report, TFR is highest in Northern Pemba (6.5 children per woman), and lowest in Dar es Salaam (3.1 children per woman). Furthermore, the report says fertility is negatively associated with the educational attainment of the mother, decreasing from 5.5 children per woman for women with no education or attended pre-primary education only to 2.3 children per woman for women with tertiary education or above.

“Women engaged in agricultural activities (farmers, livestock keepers and fishers) have a relatively higher TFR (4.9) compared to women engaged in clerks with TFR of 1.6. Fertility levels are low among women engaged in occupations that require professional training or other skills,” it says.

According to a United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) report titled “World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results”, globally, the number of women in the reproductive age range is projected to grow through the late 2050s, when it will likely peak at about 2.2 billion, up from about 2.0 billion in 2024. “Growth in the number of women of reproductive age is conducive to continuing population increase even when the number of births per woman falls to the replacement level.”

However, the report says average fertility levels are at or above 2.1 live births per woman in 45 per cent of countries and areas. It suggests that over 1 in 10 countries and areas — mostly in sub-Saharan Africa — have fertility levels of 4 births or more per woman, and this group includes the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Niger and Somalia.

“Increasing the age at first childbearing contributes to slowing population growth, reducing the scale of the investments and effort required to achieve sustainable development while ensuring that no one is left behind. If there were no births to girls under age 18, the population of countries in sub-Saharan Africa in 2054 would be 3.8 per cent smaller than it would have been otherwise,” says the report.

David Bloom, Michael Kuhn, and Klaus Prettner in their special report titled “The Debate over Falling Fertility” published in June 2025 suggest that, while the human population now exceeds 8 billion and may reach 10 billion by 2050, the momentum of growth is dissipating because of declines in its most powerful driver—fertility.

“Over the next 25 years, East Asia, Europe, and Russia will experience significant population declines,” their report says. It adds that “what this will mean for the future of humanity is rather ambiguous…[it] could hinder economic progress as there will be fewer workers, scientists, and innovators. This could lead to a paucity of new ideas, and long-term economic stagnation.” The authors note that as populations shrink, the proportion of older persons tends to expand, weighing on economies, and challenging the sustainability of social safety nets and pensions.

They argue that fewer children, and smaller populations will mean less need for spending on housing and childcare, freeing resources for other uses such as research and development and adoption of advanced technologies.

“Declines in fertility rates can stimulate economic growth by spurring expanded labour force participation, increased savings, and more accumulation of physical and human capital. Population decline may also reduce pressure on the environment associated with climate change, depletion of natural resources, and environmental degradation,” their report points out.

The authors suggest that low fertility, and depopulation can hinder economic and social progress. “Fewer births and smaller populations naturally mean fewer workers, savers, and spenders, potentially sending an economy into contraction. A shortage of researchers, inventors, scientists, and other people-based sources of innovative ideas could also hurt economic progress.”

However, the authors argue that there is nothing wrong with an economy expanding or shrinking along with its population, except the declining per capita GDP, stagnating innovation and growth, and the challenges of supporting an aging population. “Those threats have already driven some countries facing declining or low fertility to implement measures to stabilise or increase birth rates.”

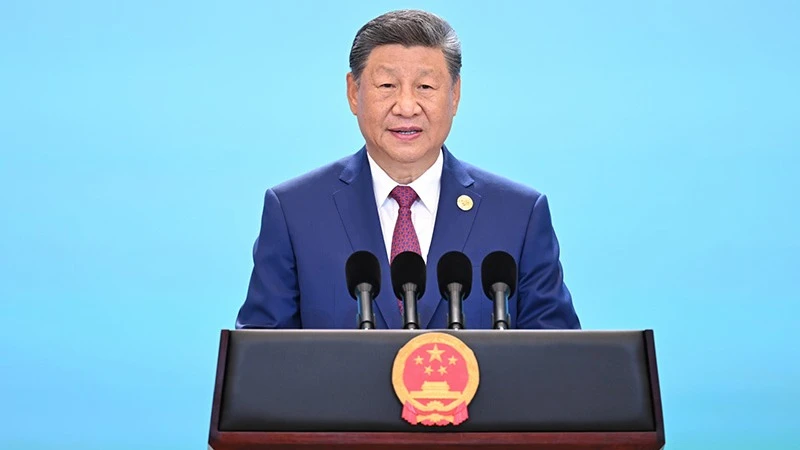

Giving examples, they say that South Korea recently reported a rise in fertility rates for the first time in nine years, China abolished its one-child policy, Japan introduced flexible work arrangements, and some European countries are overhauling their social security systems to ensure sustainability.

United Nations Population Fund (UNPF) Executive Director, Dr Natalia Kanem, in a report titled “The Real Fertility Crisis: The Pursuit of Reproductive Agency in a Changing World (2025)” says: “Our human population is the subject of growing interest – and intensifying anxiety. The concerns that draw most attention are declining fertility rates, ageing and workforce shortages, while many still argue that the greatest threat to the planet is overpopulation.”

Kanem says millions and millions of people still, therefore, cannot exercise their reproductive rights and choices. “This inability of individuals to realise their desired fertility goals is the real fertility crisis – not overpopulation or underpopulation – and we see it everywhere we look.”

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED