IUU fishing activities deny Tanzania billions from its maritime resources

ACCORDING to Sustainable Development Goal 14.4, overfishing, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities, along with destructive practices by both industrial vessels and unregulated small-scale fishers, remain major challenges globally—and Tanzania is no exception.

Efforts to combat overfishing, IUU fishing, and destructive fishing practices cannot succeed without the active involvement of local civil society and communities.

Prioritizing Tanzanian control and access to its marine resources is essential—not only for safeguarding national sovereignty but also for enhancing food security, promoting sustainable economic growth, and protecting marine ecosystems.

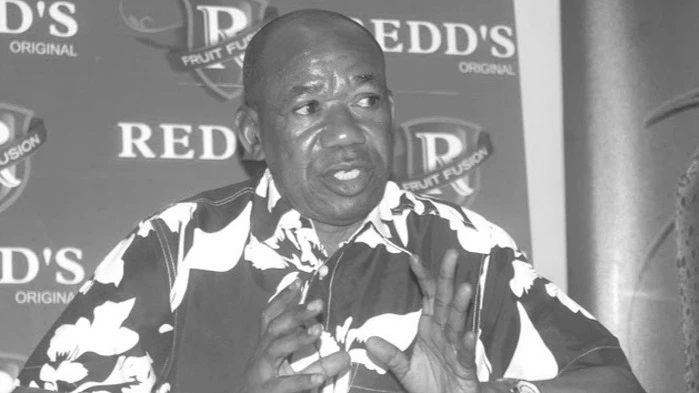

In an exclusive interview with this paper, Dr Modesta Medard, World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Tanzania, Seascape Programme Lead emphasized the organization’s on-going efforts to promote sustainable use of marine resources and combat IUU fishing.

WWF's role in combating IUU fishing

Dr Medard highlighted several key initiatives spearheaded by WWF Tanzania under the Seascape Programme, including supporting cost-effective monitoring, control, and surveillance (MCS) training, in collaboration with local fisheries management bodies such as Beach Management Units (BMUs), marine security practitioners, the Fisheries Education and Training Agency (FETA), and district authorities.

She said WWF also supply drones to government institutions to improve monitoring and control of IUU fishing activities, supporting government efforts to ratify regional and international agreements, including the Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA) and the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA).

She told The Guardian that they have been assisting in the development of Tanzania’s national plan of action to prevent, deter, and eliminate IUU fishing and conducting quarterly and semi-annual resource monitoring in Marine Protected Areas and community-led Collaborative Fisheries Management Areas (CFMAs).

Facilitating capacity-building programmes and providing equipment—such as patrol boats, engines, and life jackets—to institutions including district authorities, Tanzania Forest Services, and the Ministry of Forests in Pemba (Mkoani District).

Dr. Medard emphasized that most IUU fishing in Tanzania occurs within the country’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), primarily by foreign vessels.

In response, WWF is collaborating with the government to enhance MCS measures, including strengthening security patrols, installing surveillance systems on fishing vessels, and improving landing site management.

Because fishery resources are trans-boundary by nature, she stressed that international cooperation is essential. WWF has also been instrumental in supporting Tanzania’s participation in international treaties such as the PSMA, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and is currently assisting in the ratification of UNFSA—all aligned with the goals of the “High Seas Treaty” or “Global Ocean Treaty.”

Economic potential of EEZ resources

Dr Medard explained that Tanzania’s EEZ, which lies within the South West Indian Ocean’s rich tuna belt, holds immense potential that remains largely untapped. If fully utilized, EEZ resources can significantly benefit Tanzania in multiple ways:

“Deep-sea fishing contributes to the national GDP through raw material supply for export-oriented fish processing industries, as well as revenue from vessel licensing and taxation,” said Dr Medard, adding the sector provides jobs across the fishery value chain. According to the Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries, over 6 million Tanzanians depend on the sector, with 198,475 directly involved in fishing.

She said seafood remains a major source of nutrition for coastal communities. Seafood is rich in high-quality protein, which is essential for growth, tissue repair, and overall body function. For many coastal populations, fish is the main or only source of animal protein.

Fishing offers year-round food availability, helping to prevent hunger during times when farming or other food production is difficult especially during droughts and floods. Fishing provides income for many coastal families. That income can be used to buy other foods, healthcare, and education, which further supports nutritional well-being.

On tourism and ecology, marine biodiversity attracts tourists and provides critical ecological services, while also preserving cultural heritage.

Parliamentary findings on IUU fishing losses

On February 13, 2025, the National Assembly revealed that Tanzania loses approximately 15.16bn/- annually due to illegal fishing, unregistered vessels, and poor data collection.

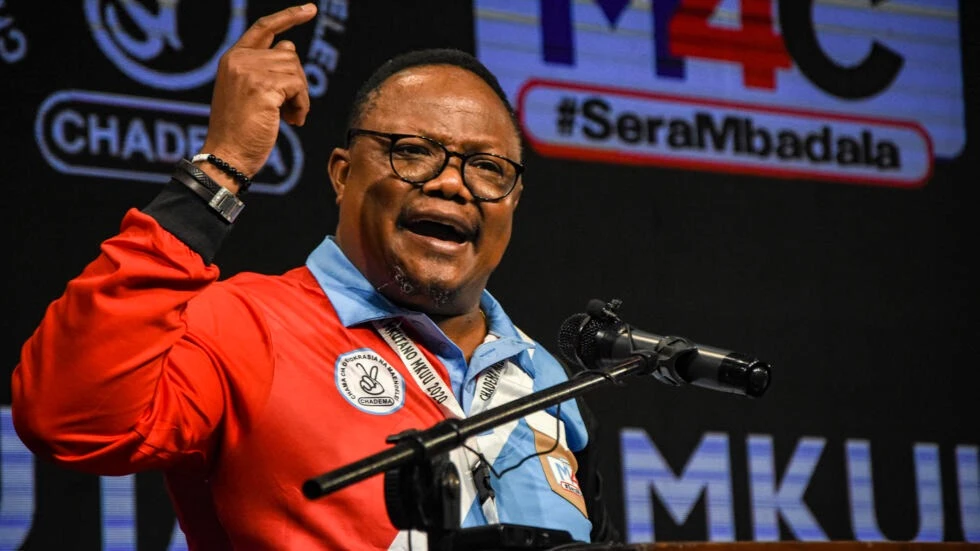

The report, tabled and approved by the National Assembly, assessed the registration of vessels and fishers, as well as the monitoring and coordination of fishing activities. Public Accounts Committee Chairperson Naghenjwa Kaboyoka (Special Seats, Chadema) cited numerous shortcomings such as unlicensed fishing activities and poor coordination of operations across lakes and the ocean, absence of seasonal fishing restrictions as well as inadequate patrols to deter illegal practices.

She noted that many vessels are unregistered or lack proper licenses, leading to inaccurate data and loss of government revenue—including from the Tanzania Shipping Agencies Corporation (TASAC) and the Tanzania Revenue Authority (TRA).

The report revealed a widespread presence of unregistered fishing vessels operating across Lake Tanganyika, Lake Victoria, and the Indian Ocean.

Among these, Lake Victoria recorded the highest proportion, with 67 percent of its fishing vessels unregistered. This was followed by Lake Tanganyika at 61 percent, and the Indian Ocean at 42 percent.

The audit further highlighted gaps in resource management infrastructure, noting that 45 percent of Lake Tanganyika’s landing sites lack Beach Management Units (BMUs), while 36 percent of landing sites along the Indian Ocean remain similarly unmanaged.

“The lack of oversight at these landing sites has contributed to a rise in unregistered fishing vessels, which in turn fuels illegal fishing and denies the government substantial revenue,” said Kaboyoka.

Additional findings pointed to the ongoing sale of undersized fish, particularly in marine areas. While this issue has reportedly declined in inland lakes, it remains a significant problem in coastal zones, threatening both the sustainability of the fishing sector and food security for local communities.

Kaboyoka also cited an official from the Ministry, explaining that PO-RALG is responsible for licensing vessels smaller than 11 meters, which make up about 70 percent of the national fishing fleet, while the Ministry of Fisheries licenses the remaining 30 percent, comprised of larger vessels.

The audit also uncovered continued misuse of legally acquired fishing nets, which are often repurposed to catch undersized fish, despite regulations.

Although the government has made efforts to strengthen inspections and patrols, these persistent challenges continue to undermine enforcement efforts and weaken overall governance in the fisheries sector.

The report concludes with a strong call to action, emphasizing the need for increased investment by the government and stakeholders to enhance regulation, promote sustainable practices, and unlock the full economic and ecological potential of the fisheries sector.

The report highlighted that vessel licensing is split between PO-RALG (for vessels under 11 meters, which make up 70 percent of the fleet) and the Ministry of Fisheries (for the remaining 30 percent). However, enforcement challenges—like the misuse of legal nets to catch undersized fish—remain rampant.

A report released in early 2024 by the UK-based Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) revealed severe IUU fishing and human rights violations by Chinese vessels operating in the Southwest Indian Ocean, including Tanzanian waters.

EJF's report, titled “Tide of Injustice: Exploitation and Illegal Fishing on Chinese Vessels in the Southwest Indian Ocean,” implicated China’s distant-water fleet—the largest globally by vessel count and catch volume—in widespread IUU fishing and abuses. These practices threaten global fishery sustainability, endanger marine ecosystems, and undermine national and international governance.

Government actions

In his budget speech for the 2024/2025 fiscal year, delivered on June 27, 2024, Minister for Livestock and Fisheries Abdallah Hamis Ulega announced that by April 2024, the Deep Sea Fishing Authority (DSFA) had issued 67 licenses for deep-sea fishing.

Only one of these was to a domestic fleet, while the remaining 66 were to foreign fleets.

Dr. Emmanuel Sweke, Director General of the Tanzania Deep Sea Fishing Authority (DSFA) stated that although Tanzania has not yet ratified the Ports State Measures (PSMA), the process is underway.

PSMA plays a crucial role in fighting IUU fishing by restricting port access to non-compliant vessels and preventing them from entering international markets.

Formed in 2010 under the Deep Sea Fishing Authority Act (Cap. 388), the DSFA plays a key role in regulating Tanzania’s deep-sea fishing activities.

The richness of Tanzania’s marine resources

Tanzania is endowed with a diverse marine environment that includes a 1,424-kilometer coastline and numerous islands stretching from Tanga to Mtwara. Its marine area spans approximately 241,500 square kilometers—nearly 20 percent of the country’s landmass.

Coastal and marine ecosystems include mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass beds, sandy beaches, rocky shores, and coastal forests. These habitats are vital for biodiversity conservation, food security, and climate resilience.

Tanzania stands to gain immensely—economically, socially, and environmentally—if it can curb IUU fishing and fully harness the potential of its marine resources. Strengthening monitoring, surveillance, governance, and international cooperation is not just a necessity—it is an urgent imperative.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED