Kigongo-Busisi crossing: Chaos, delays and hope for a new bridge

IN the pre-dawn hush of Nyegezi Bus Terminal, the anticipation of a journey ahead often carries a mix of excitement and routine. Boarding a familiar bus at 9:30am, bound for Bukoba, the expectation is a seamless voyage reminiscent of past travels through the Lake Zone's scenic tapestry—Buseresere, Chato, Bwanga, Geita, and onwards via Runzewe and Muleba.

However, as the bus approaches the Kigongo-Busisi ferry terminal, a starkly different reality unfolds.

By 10:45am, the terminal is already a hive of activity, but not the orderly kind one might hope for. Passengers are instructed to disembark and purchase separate ferry tickets—400/- per person—a process that, while seemingly straightforward, adds an unexpected layer of hassle.

The waiting area is a sea of weary travelers, their faces etched with frustration and fatigue. Outside, a serpentine line of vehicles—semi-trailers, buses, private cars, motorcycles—stretches nearly two kilometers, a visual testament to the bottleneck that this crossing has become.

The scene at the water's edge is equally disheartening. Of the four ferries that once plied these waters—MV Mwanza, MV Misungwi, MV Sengerema—only one remains operational. The others sit idle, their hulls bearing the scars of time and neglect.

The official explanation points to invasive water hyacinths clogging the engines, a persistent menace that has plagued these vessels for years. Yet, as the hours tick by with no ferry in sight, the patience of those awaiting passage wears thin.

By 10:00am, the waiting area has transformed into a cauldron of simmering discontent. Parents struggle to soothe restless children, elderly passengers shift uncomfortably in their seats, and the collective murmur of complaint grows louder.

The lack of communication from ferry authorities only fuels the frustration. Ticketing staff, when approached, offer little more than indifferent shrugs, leaving travelers feeling abandoned in their plight.

As hunger sets in, some brave the onboard canteen, only to be met with exorbitant prices—8,000/- – 9,000/- for a simple plate of rice and fish. For many, this is an unaffordable luxury, adding a layer of economic strain to an already taxing ordeal.

The hours drag on. Conversations among passengers reveal a shared sense of exasperation. Parents struggle to keep their restless children entertained, elderly travelers shift uncomfortably in their seats, and traders, whose livelihoods depend on timely arrivals, watch helplessly as their goods risk spoilage.

“This crossing used to be so efficient,” one traveler laments, shaking his head. “Now, it’s nothing but delays and excuses. Corruption has ruined everything.” Another passenger, a middle-aged businessman clutching a bag of documents, interjects.

“We know what’s happening here. Money meant for maintaining these ferries disappears into pockets. They collect revenue, but where does it go? If they had managed this properly, we wouldn’t be stuck here for ten hours.”

Frustration builds, and theories swirl. Some believe the ferry delays are politically orchestrated to justify the need for the new bridge. Others argue it’s sheer government inertia, a failure to acknowledge the impact of these daily bottlenecks on the economy.

A trader from Geita, carrying sacks of fresh produce, voices her fears. “By the time I get to Bukoba, my fruits will be half-rotten. Who will compensate me? Transport should help business, not kill it.”

Another passenger, a driver ferrying goods from Mwanza, echoes her concerns. “Fuel is expensive. Every extra hour we waste here is money lost. If the ferries were efficient, businesses would thrive. But here we are, wasting an entire day.”

He gestures toward the idle ferries docked nearby. “These could be running if they were maintained. Instead, we’re all suffering because someone, somewhere, isn’t doing their job.”

Finally, after more than 4 grueling hours, the ferry arrives. A sense of relief washes over the crowd, but it’s laced with frustration. The journey is far from over.

As the ferry sets sail, rain begins to fall, the droplets merging with the dampened spirits of those on board. The crossing should have been a 15-minute formality, not a drawn-out ordeal.

The promise of the new bridge lingers in conversation—could it finally end this chaos? If completed and properly managed, it could slash travel time, cut costs, and revitalize trade. But until then, passengers remain at the mercy of a crumbling system, where inefficiency reigns and accountability is scarce.

The Kigongo-Busisi crossing, once a vital artery for trade and travel in the Lake Zone, has undeniably become a chokepoint. The economic ramifications are profound—lost productivity, increased transport costs, and a stifling of regional commerce. The situation begs the question: how did it come to this?

In recent years, the challenges have mounted. The aging ferry fleet struggles to keep pace with the growing demand, and mechanical failures have become commonplace.

The invasive water hyacinths exacerbate these issues, their rapid proliferation clogging engines and hindering navigation. Efforts to combat the infestation have been sporadic and largely ineffective, leaving ferry operators in a constant battle against nature.

Compounding these operational woes are systemic issues of mismanagement and corruption. Investigations have uncovered fraudulent practices in ticket sales, with reports of tickets being sold multiple times and government vehicles bypassing fees altogether. Such malpractices not only drain vital resources but also erode public trust in the ferry system.

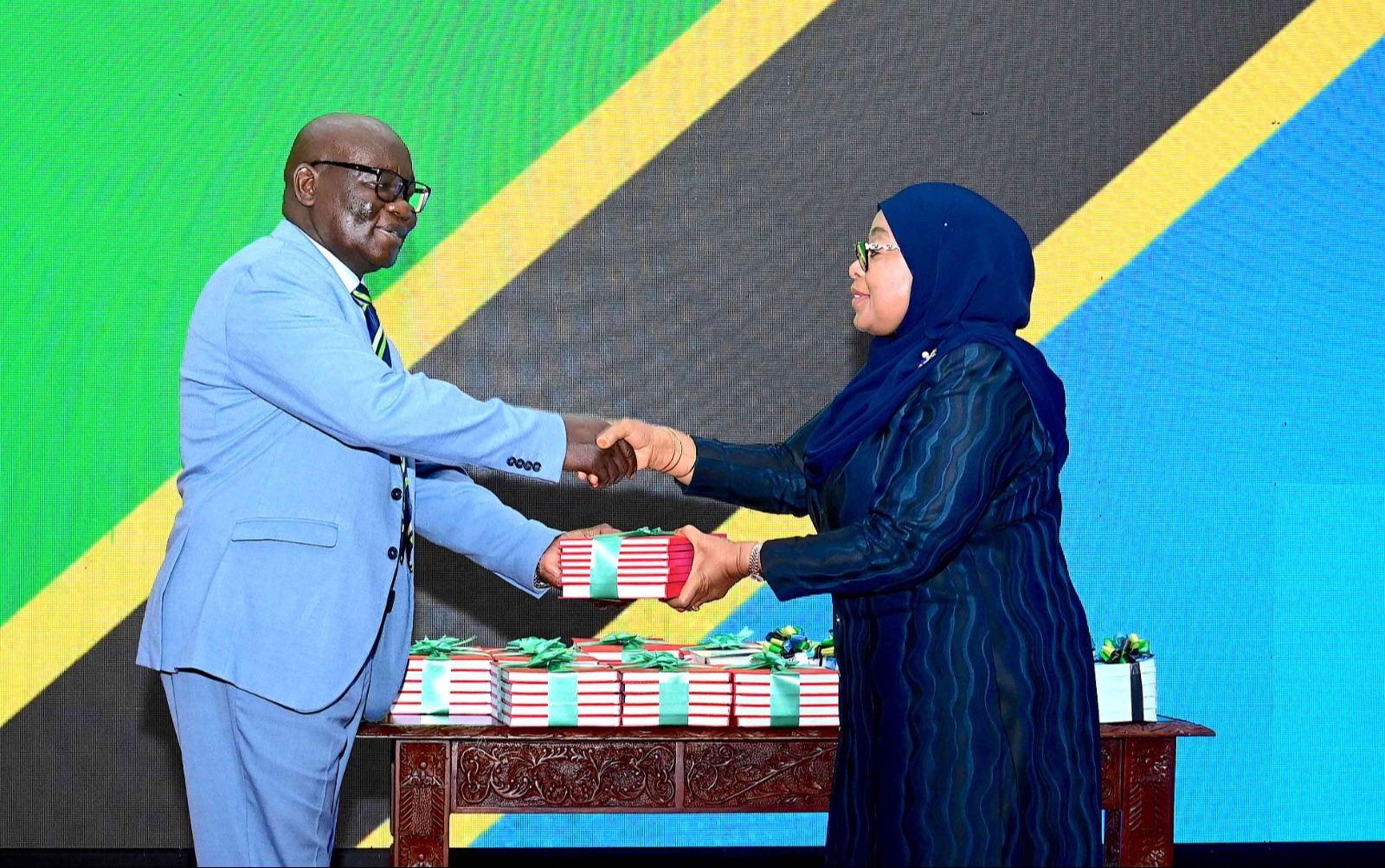

Amidst this turmoil, a beacon of hope emerges on the horizon—the John Pombe Magufuli Bridge. Spanning 3.2 kilometers across the Gulf of Mwanza, this engineering marvel promises to revolutionize transport in the Lake Zone.

Deputy Permanent Secretary of Works, Dr. Charles Msonde, has announced that the 3 km J.P. Magufuli Bridge at Kigongo-Busisi will officially open on April 30, with one lane accessible to vehicles from April 10.

Currently, ferries take up to two hours to cross, but the bridge will cut this to just three to four minutes, easing transport on the Usagara-Sengerema-Geita Highway. With construction at 97% completion, the project is set to boost trade and connectivity in the Lake Victoria Corridor.

It forms a critical link in the 90-kilometer Usagara-Sengerema-Geita highway, enhancing connectivity between Sirari on the Kenya-Tanzania border and Mutukula on the Uganda-Tanzania border. This integration is poised to bolster regional trade, stimulate economic growth, and improve the livelihoods of countless individuals.

However, the transition from ferry to bridge is not without its challenges. The construction process has faced delays, and questions linger about the maintenance and management of such a significant infrastructure project. Moreover, the fate of the ferry workers and the future role of the ferries themselves remain uncertain.

Looking beyond Tanzania's borders offers valuable insights. In Hong Kong, the Star Ferry operates with remarkable efficiency, thanks to rigorous maintenance schedules and integration with other transport modes.

Norway's adoption of battery-powered ferries showcases a commitment to innovation and environmental stewardship. Even closer to home, Kenya's Likoni Ferry has seen improvements through substantial investments in new vessels and enhanced maintenance practices. For Tanzania, the path forward requires a multifaceted approach.

For Kigongo-Busisi, the lesson is clear: efficiency is not a luxury—it’s a necessity. A well-run ferry system isn’t just about convenience; it fuels trade, cuts costs, and keeps daily life moving.

Yet here, mismanagement and neglect have turned a vital transport link into a bottleneck of frustration. The new bridge offers hope and a chance to rewrite this broken narrative.

But even with it, Tanzania must rethink its ferry operations—invest in maintenance, enforce accountability, and embrace innovation. Without action, history will repeat itself, and the promise of progress will remain just that—a promise, never fully realized.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED