Why preventing sickle cell is a priority for Tanzania

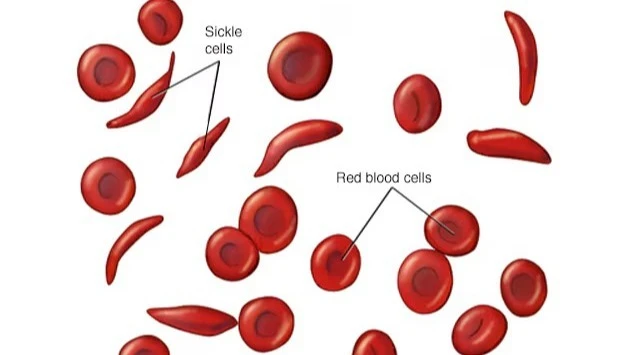

IN Tanzania, sickle cell disease (SCD) casts a long shadow over families and the healthcare system, a beacon of hope is emerging: a proactive movement focused on prevention.

Data from the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) shows that sickle cell disease claims the lives of 7 percent of Tanzanian children before their fifth birthday and an alarming 11,000 to 14,000 new-borns are diagnosed with the condition annually.

A significant 20 percent of the country’s population carries the sickle cell trait, many unknowingly, placing the country as the fifth highest globally and fourth in Africa for prevalence.

Historically, stigma and misconceptions surrounding sickle cell have hindered effective management. Individuals testing positive often faced social isolation and were tragically kept from seeking necessary medical care.

However, a concerted effort is underway to dismantle these barriers through widespread education and awareness campaigns spearheaded by Dr Agnes Jonathan, sickle cell project manager at MUHAS.

Through the campaign, Tanzania is shifting its focus towards prevention, aiming to curb the devastating impact of this genetic blood disorder.

“The sheer scale of this issue demands serious investment. Sickle cell is not just a personal tragedy; it is a significant public health concern that requires a multi-pronged approach, with prevention at its heart,” said Dr Jonadhan.

“We've begun working closely with associations of people living with sickle cell disease, engaging communities directly, and collaborating with influential religious leaders,” she explains adding: “Our goal is to empower every Tanzanian with knowledge about this condition and encourage them to get tested to understand their status.”

Dr Jonathan said the emphasis on testing is a cornerstone of the prevention strategy. Understanding one's carrier status becomes critical, particularly when individuals reach marriageable age.

According to her, informed decisions about family planning can significantly reduce the likelihood of passing on the sickle cell gene.

“Knowing if you carry the trait empowers you to make responsible choices about your future family. It allows couples to understand the risks involved, how the trait is inherited and ultimately, how to prevent its transmission to their children.”

Beyond pre-conception awareness, the sickle cell project at MUHAS focuses on early detection in new-borns whereas a pilot programme has commenced in Dar es Salaam and Mwanza, offering sickle cell testing to new-borns, with hopeful plans to expand the crucial service to other regions across Tanzania.

“Early diagnosis is transformative. It allows children with sickle cell to access timely and appropriate medical care, significantly improving their chances of survival and quality of life,” she told The Guardian.

Innovative strategies are being explored to maximize reach. One promising avenue involves leveraging the existing infrastructure of immunization centres. These facilities, routinely visited by parents with young children for vaccinations, present an ideal opportunity to integrate sickle cell screening.

Drawing parallels with the successful HIV response in Tanzania, the project aims to incorporate sickle cell awareness and testing into existing healthcare frameworks.

“We can learn a great deal from the experience and infrastructure established for HIV programmes," noted the project manager, “Integrating a sickle cell component will allow us to reach a larger segment of the population efficiently.”

While prevention remains paramount, the project also addresses the critical need for improved treatment and management for those already living with sickle cell.

Access to essential medications like hydroxyurea, a medication that helps reduce the frequency and severity of pain crises, remains a challenge due to cost and availability.

There is a strong advocacy push to make this drug more affordable and accessible, mirroring the success of antiretroviral drugs for HIV. The vision is to seamlessly integrate sickle cell services into the broader maternal and child health framework.

The hope is that every pregnant woman will receive comprehensive education and testing and every new-born will be screened, ensuring early intervention and preventing the devastating consequences of sickle cell disease.

Dr. Jonathan's commitment to tackling sickle cell extends to exploring advanced therapies.

While bone marrow transplantation is currently available, the potential of gene therapy, a less invasive approach that aims to correct the faulty gene responsible for sickle cell, offers hope for a future where sickle cell disease is not a life sentence.

Tanzania's sickle cell disease plan focuses on strengthening comprehensive care, including specialized services and improved services in primary health care facilities.

SCD interventions are part and parcel of the National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases. SCD medicines are integral to the updated essential medicines list and the National Standard Treatment Guidelines of the ministry.

“The Ministry is working to strengthen SCD comprehensive care programs at all levels. At the moment, a consolidated range of services, including definitive diagnosis, is provided at the Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH),” she said.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 300,000 children are born with SCD worldwide each year. With inadequate diagnostic facilities, support, and proper treatment, 50-90 percent of these children may die from the disease in their childhood.

The disease contributes to 6.4 percent of under-five mortality in Africa. The infant birth rate for the disease in Tanzania is approximately 6 per 1,000 per annum, which translates to roughly 8,000 - 11,000 infants per year. The East Coast, Southern, and Lake regions are more affected.

WHO recommends that countries with an annual SCD infant birth rate above 0.5 per 1,000 should establish national programmes for the management and prevention of the disease.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED