The hidden toll of uterine fibroids on Tanzanian women

EVERY month, 33-year-old Happy Dismas loses up to four days of work due to debilitating menstrual bleeding caused by uterine fibroids. “After my first surgery in 2021, I thought I was done. But they came back,” she says.

Now, she’s reluctant to undergo another operation, fearing recurrence. The other option is to remove her uterus, but she’s not ready to consider it.

Happy’s story is far from unique. Across Tanzania, thousands of women bear the physical, emotional, and financial weight of uterine fibroids—non-cancerous tumours that grow in or around the uterus. Though common, especially among African women, fibroids remain underdiagnosed, undertreated, and shrouded in silence.

A widespread but invisible crisis

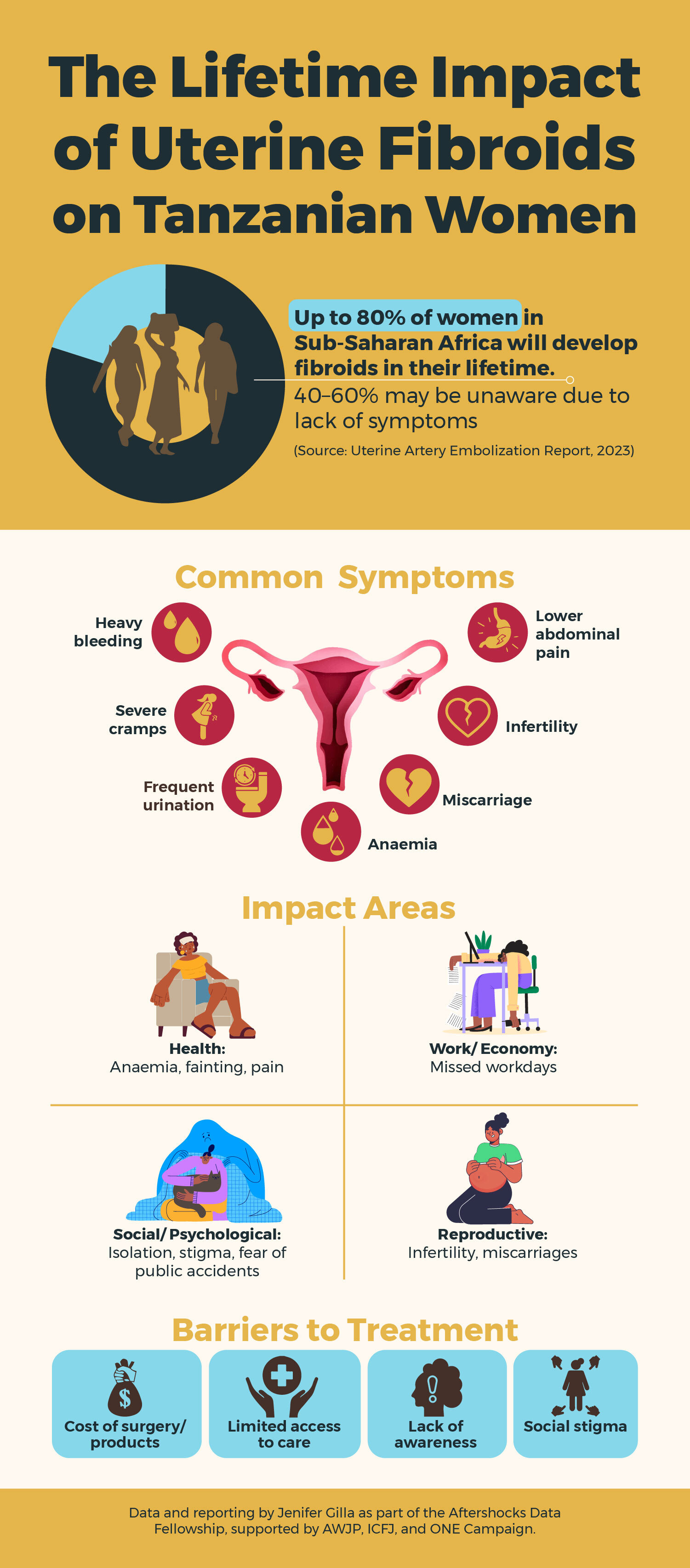

Studies show that up to 80 percent of African women will develop fibroids in their lifetime, with the highest rates reported in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet fibroids are often normalised, dismissed as “just period pain”, or neglected entirely in reproductive health policies. According to the 2023 report on Uterine Artery Embolisation in Tanzania, the consequences are not only medical but also deeply personal and economic.

The Epidemiology of Uterine Fibroid in Black African Women report shows that lifestyle factors, such as vitamin D deficiency and limited physical activity, increase the risk of fibroids. African women experience higher fibroid incidences, yet they face significant barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment, emphasising the need for greater awareness and accessible healthcare options.

Fibroids can reduce productivity, impacting women economically, as some must halt income-generating activities due to pain.

Women like Luciana Kavishe from Mbezi, Dar es Salaam, experience life-altering symptoms. “My haemoglobin once dropped to 5. I couldn’t walk. I used maternity pads to manage the bleeding when I could afford them. Other times, I used kangas,” she says. The heavy bleeding, abdominal pain, dizziness, and even fainting forced her into debt and isolation.

Maria Khamisi, 38, didn’t know fibroids were behind her repeated miscarriages until she collapsed in early 2023 and was taken to a gynaecologist. “My husband left me. He said I was cursed,” she recounts. With no insurance and limited income, she relied on her family to fund an emergency hysterectomy. The decision left her infertile—a loss she believes could have been avoided with earlier intervention.

Why are fibroids still so neglected?

“Many women don’t realise they have fibroids until the symptoms are severe,” explains Dr. Lilian Mnabwiru, a gynaecologist at Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH).

Symptoms range from heavy periods and fatigue to infertility and severe anaemia. Fibroids may grow silently for years, often accelerated by hormones like oestrogen and progesterone, especially in women aged 18 to 40.

Despite their prevalence, fibroids remain overlooked in public health planning. Experts cite gender bias, inadequate access to gynaecological care, and the societal normalisation of women’s pain as root causes. “By the time many women seek help, their condition is already critical,” adds Dr. Gregory Ntiyakunze of Aga Khan Hospital.

Dr. Elius Kweyamba of St. Francis Hospital in Morogoro estimates that 40–60% of Tanzanian women may have fibroids without being aware of it. Risk factors include genetics, vitamin D deficiency, diet, low physical activity, and late pregnancies. Policy changes are equally essential.

The cost of delay

The economic cost is steep: time off work, recurring medical bills, and unaffordable sanitary products. For many, this burden is compounded by shame, anxiety, depression, and broken relationships—mental health effects rarely addressed in clinical settings.

“My husband left me. He said I was cursed,” Mary Khamisi says. She eventually had to undergo a hysterectomy, funded through contributions by friends and relatives. She is now unable to have children — a heartbreaking outcome she believes could have been avoided with earlier diagnosis and treatment. In Tanzania, where societal expectations often equate a woman’s value with her ability to bear children, this loss has subjected her to heightened stigma and judgement.

A new hope: Uterine Artery Embolisation (UAE)

There is a glimmer of hope for women like Mary, Happy and Lucian, however, thanks to efforts at Tanzania’s top public hospital. Between 2019 and 2022, a pioneering team at Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) and MNH successfully introduced uterine artery embolisation (UAE). This minimally invasive procedure treats fibroids without surgery. Thirty-eight patients received UAE during this pilot phase, achieving a 97.3 percent technical success rate and only one minor complication.

The UAE procedure works by inserting a catheter into a blood vessel (typically in the wrist or groin) and releasing tiny particles that block blood flow to the fibroids, causing them to shrink. The benefits are significant: no need for hysterectomy, faster recovery, fewer complications, and preserved fertility. However, it’s not suitable for all patients and requires individual assessment.

For women like Happy and Luciana—who fear repeated surgeries—the UAE offers a non-surgical alternative with real promise. Yet access remains limited, and the procedure is still not widely available or covered under most health insurance plans in Tanzania.

The cost of silence

Beyond health risks, fibroids undermine women’s productivity, income, and self-worth. “My supervisors understood at first,” says Happy. “But now, they’re frustrated. I’m left to pick up the backlog alone.”

Luciana adds, “I live in fear. I can’t wear light-coloured clothes. I avoid parties. I feel trapped in my own body.”

The psychological burden is enormous. Women report shame, anxiety, depression, and broken relationships — all of which are rarely addressed in clinical settings.

What needs to change

Tackling the fibroid crisis in Tanzania requires more than treating symptoms — it demands systemic change. According to health experts, one of the most urgent steps is launching nationwide public education campaigns to help women recognise early signs of fibroids and seek timely care. Many women endure pain for years without knowing what’s wrong, often mistaking their symptoms for normal menstrual discomfort.

Beyond awareness, there’s a pressing need to invest in diagnostic tools and less invasive treatment options. Uterine artery embolisation, for instance, has been successfully used in other countries to treat fibroids without the risks and recovery time of surgery, yet it remains largely inaccessible in Tanzania due to cost and limited availability.

Mental health is another piece of the puzzle. For women like Luciana and Maria, the emotional toll of living with fibroids — from isolation and anxiety to relationship breakdowns and financial stress — is as devastating as the physical symptoms. Experts stress the importance of integrating psychosocial support into gynaecological care so that women aren’t left to manage the burden alone.

Way forward

The success of Uterine Artery Embolisation (UAE) at Muhimbili has demonstrated what is possible when innovation, access, and gender-sensitive care come together. But experts say this success story shouldn’t end within the walls of one hospital.

Building on the MUHAS/MNH model, they envision a broader transformation: scaling up interventional radiology training and infrastructure so that the UAE becomes available in more regions, not just the capital. They call for nationwide awareness campaigns to ensure that women recognise fibroid symptoms early, and that clinicians know surgery isn’t the only option.

There’s also a push to integrate UAE and other fibroid treatments into national insurance schemes and reproductive health policies, following the example of countries like South Africa. And with mobile health initiatives proving effective in places like Uganda, public-private partnerships could help bring these services closer to underserved communities.

But treatment must go beyond the physical. In Kenya and Uganda, psychosocial support and peer networks are helping women reclaim their emotional well-being after years of suffering in silence. Tanzania can learn from these approaches to ensure care is truly holistic.

From a single success, Tanzania has a chance to build a national model—one that puts women’s voices, bodies, and rights at the centre of reproductive health. Achieving this will take more than medical tools. It will require political commitment, policy reform, and a cultural shift that breaks the silence around menstrual and reproductive health.

As Dr. Lilian Mnabwiru aptly said, “We must normalise talking about menstrual health and ensure that no woman suffers in silence.”

This article was produced as part of the Aftershocks Data Fellowship (22-23) with support from the Africa Women’s Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with The ONE Campaign and the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ).

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED