African Union now backs shift to equal earth map, challenges centuries of distorted views of Africa

IT might look like a small detail in the grand scheme of global politics—just a map, some might say—but the African Union’s latest endorsement tells a much bigger story.

By joining the campaign to replace the 16th -century Mercator projection with the Equal Earth map, the AU is not merely supporting a more accurate visual of the world. It is, in its way, calling for a psychological and political reset on how Africa is perceived, both within the continent and far beyond its shores.

The Mercator projection, created by Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569, was a revolutionary tool for navigation at the time. However, its utility for sea travel came at a cost: it dramatically distorted the relative sizes of landmasses.

Europe and North America were enlarged, while Africa—immense and central to global geography—was reduced in size. The effect, over centuries, has been more than aesthetic.

In classrooms, government offices, and media representations, Africa has consistently been portrayed as smaller and somehow less significant, a cartographic slight that has subtly shaped global attitudes.

“People think maps are neutral, but they are never just about geography,” AU Deputy Chairperson, Selma Malika Haddadi told Reuters. “They shape how we see the world and our place in it.” That sentiment echoes what many African historians and sociologists have long argued: representation—visual, cultural, political—affects how nations perceive themselves and how others engage with them.

The call to “Correct the Map,” led by advocacy groups Africa No Filter and Speak Up Africa, is part of a growing movement to reclaim Africa’s narrative. The Equal Earth projection, developed by cartographers Bojan Šavrič, Tom Patterson, and Bernhard Jenny in 2018, preserves the true relative sizes of continents while maintaining a visually familiar shape of the Earth.

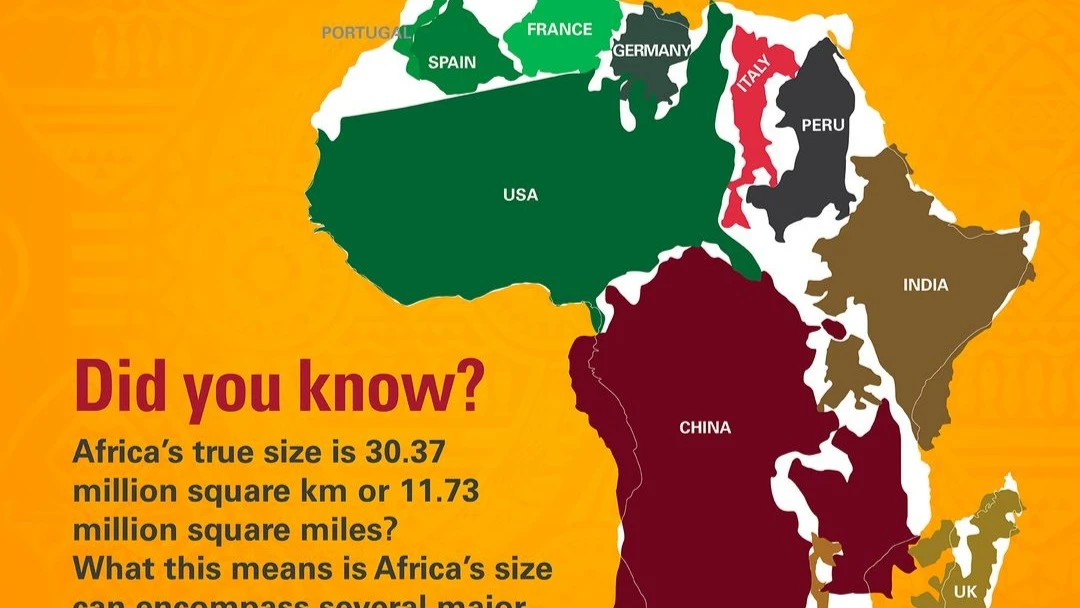

Under this projection, Africa’s sheer scale is unmistakable—large enough to contain the continental United States, China, India, and much of Europe combined.

It’s not hard to imagine the impact of this change in classrooms. A child looking at an Equal Earth map will see their continent not as a peripheral landmass dwarfed by the northern hemisphere, but as one of the dominant features of the globe.

It’s a subtle yet profound shift in perspective. As South African Geographer Professor Lindy Mavimbela puts it, “Cartography has always been political. The choice of projection tells you who is at the center and who is at the margins. We’ve lived too long with Africa at the margins.”

The map change, of course, is symbolic. Symbols do not build infrastructure, overhaul education systems, or negotiate trade agreements. But symbols can galvanize mindsets, and mindsets can drive action.

In that sense, the AU’s endorsement is less about cartographic purity and more about positioning Africa in its rightful place—literally and metaphorically—at the center of global affairs.

For too long, the mental image of Africa has been shaped by external narratives. The colonial era did not just impose foreign borders, many of them bizarrely straight lines cutting through ethnic and ecological realities; it also imposed a certain way of seeing Africa.

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, where European powers carved the continent into colonies without African representation, created geopolitical lines that still define maps today. The Mercator projection became another layer of that skewed vision, quietly reinforcing the idea of a smaller, more manageable, less threatening Africa.

This distorted worldview still influences the policies of donor agencies, trade partners, and even African governments themselves. In the words of Senegalese development economist Dr. Amadou Sy, “If you’re used to thinking of Africa as small, you’re more likely to think of it as dependent.

You underestimate its market size, its labor force, and its strategic significance.” That perception gap has real consequences, from foreign investment decisions to the allocation of global climate funding.

Correcting the map is also a reminder of Africa’s growing demographic and economic weight. By 2050, the continent will account for a quarter of the world’s population. It holds 30 percent of the world’s mineral reserves, vast tracts of arable land, and immense renewable energy potential.

And yet, in global negotiations—from climate talks to trade summits—Africa is still too often treated as an afterthought or a junior partner.

The Equal Earth map does not magically erase the deeper structural issues Africa faces: economic dependence on former colonial powers, unequal trade terms, persistent brain drain, and governance challenges.

Nonetheless, it can serve as a visual anchor for a new mindset, one that demands policy frameworks matching the continent’s true scale and potential. That shift in mindset is not only for the outside world—it is for Africans themselves.

There’s a personal dimension to this. Talk to young African professionals who studied abroad, and many will tell you of the dissonance they felt seeing their continent misrepresented in classrooms and textbooks. Some recall being told, explicitly or implicitly, that opportunities for real innovation or leadership lay elsewhere.

Others speak of returning home brimming with skills, only to find systems that sidelined them or undervalued their expertise. As Nigerian sustainability engineer Chidiebere Okekeozor notes, “The map is part of the same problem—it’s a worldview problem. We have to change the way we see ourselves before we can change the systems around us.”

In that light, the AU’s map campaign could be read as part of a broader effort to reclaim agency over Africa’s future. Agenda 2063, the AU’s long-term vision, speaks of “an integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa, driven by its citizens.” Such a vision requires not only political will and economic reform, but also cultural and psychological realignment. A correct map is a small but potent tool in that process.

Yet there is also a note of caution. Changing the projection in schools and official documents will mean little if it is not accompanied by tangible reforms in education, governance, and economic sovereignty.

As Kenyan advocate Ibrahim Emali Otiende bluntly put it in response to the AU’s announcement, “Focus on real issues. How is a map an issue?” His skepticism reflects a broader public demand: symbolism must be matched by substance.

Still, the power of the image should not be underestimated. History is full of examples where shifts in symbols paved the way for power shifts. The world map, in its current form, is one of the most reproduced and recognized images in human history. Altering it is not a cosmetic act—it is a cultural intervention.

There is also the matter of global adoption. While African governments and schools can adopt the Equal Earth projection domestically, the larger battle is to get it recognized in international institutions, textbooks, and digital platforms. This will require advocacy, negotiation, and perhaps some strategic persuasion of mapmakers and tech giants alike.

In the end, whether the Equal Earth map becomes the new norm may depend less on the AU’s declarations and more on whether this initiative sparks sustained momentum across sectors—education, media, diplomacy, and business. If it does, the ripple effects could be significant.

Perhaps, years from now, a new generation of African students will grow up never knowing that their continent was once drawn smaller than it is. They will simply take it for granted that Africa is vast, central, and integral to the world’s future—because that’s what they’ve always seen on the map.

And perhaps that subtle shift will shape the kind of leaders they become, the policies they demand, and the place Africa claims in the global order. For now, the AU has placed its marker. The rest of the world—and indeed, the rest of Africa—will decide whether to follow.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED