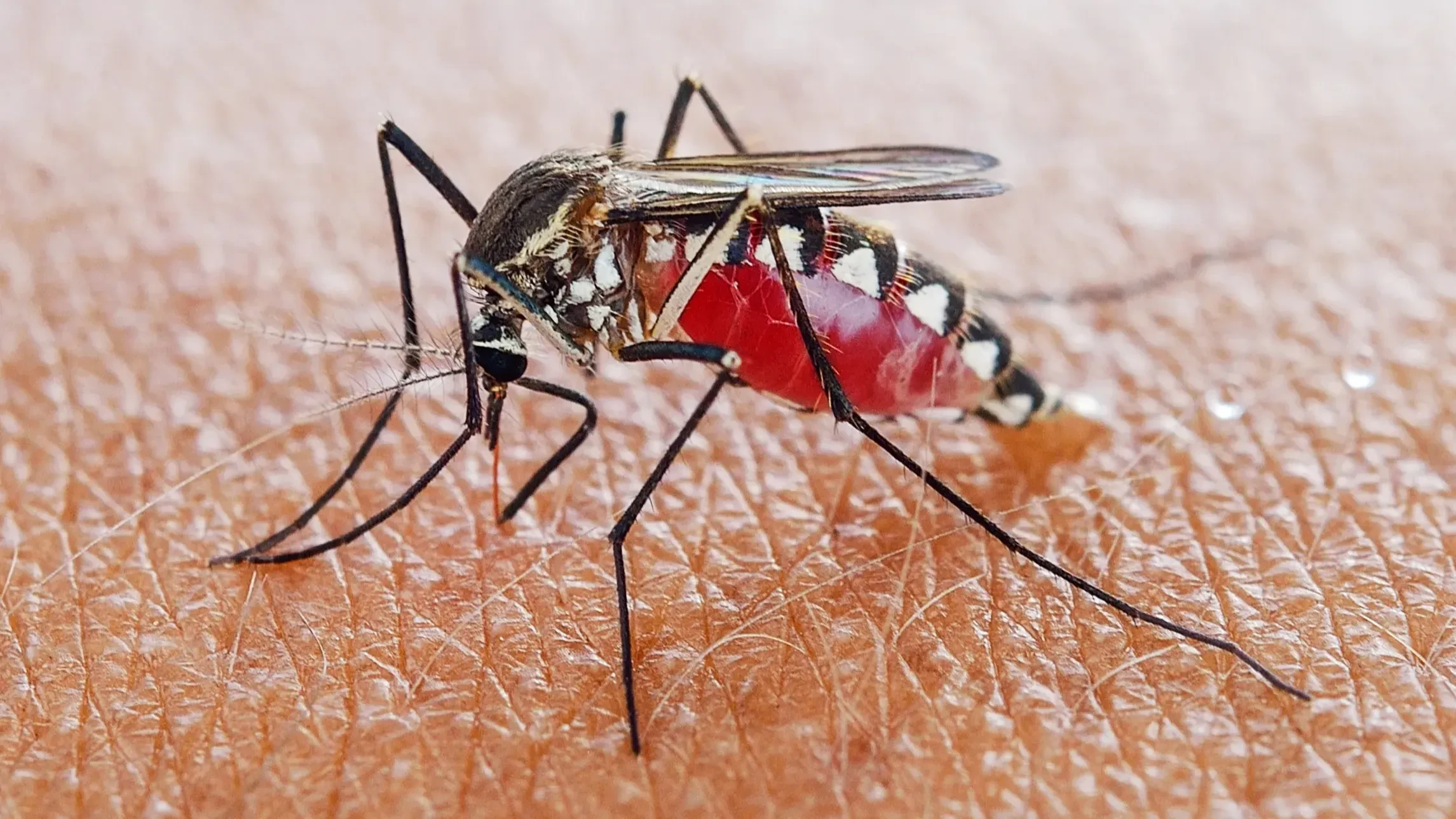

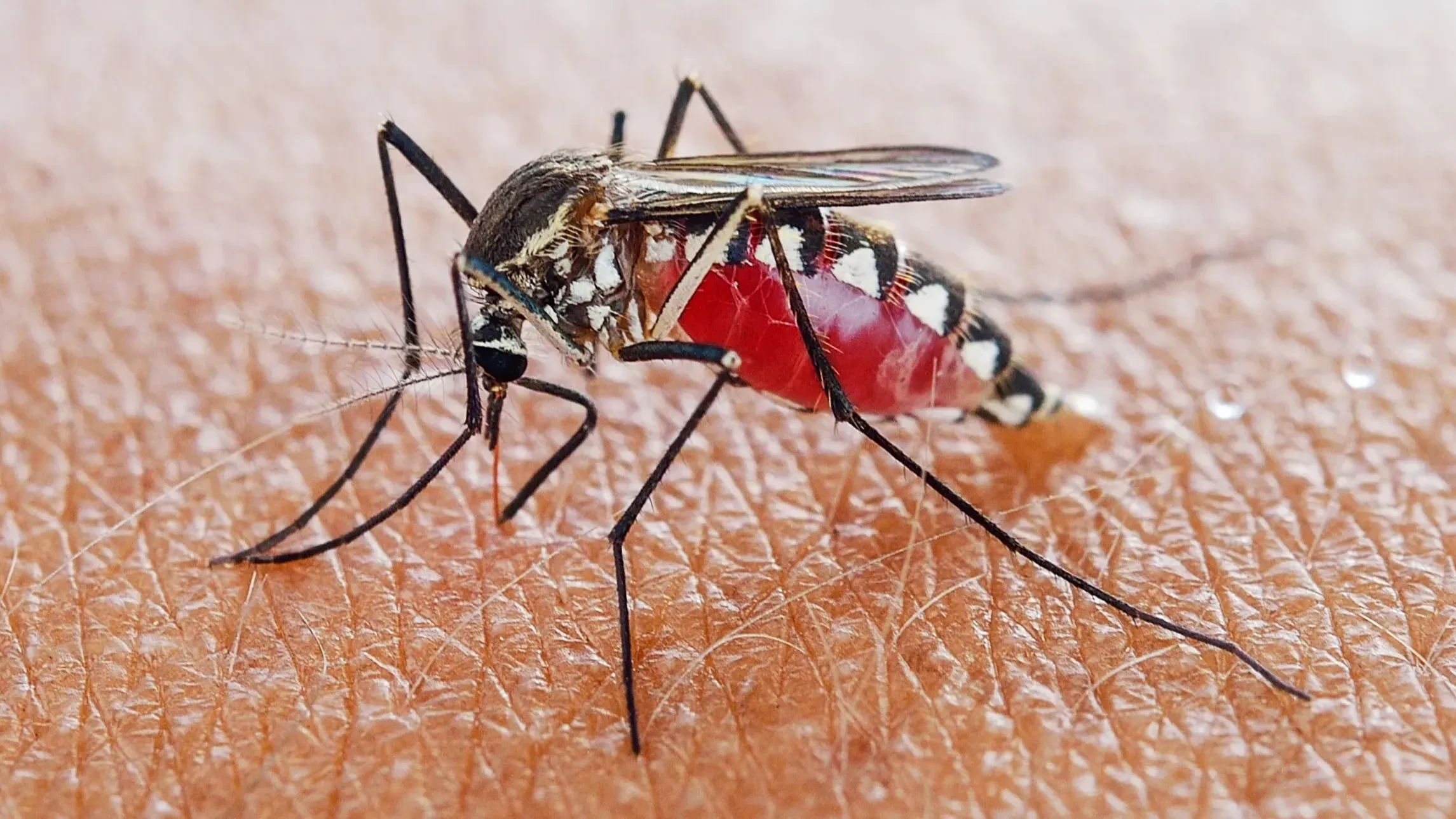

'Mosquitoes now resisting all pyrethrum insecticides‘

MOSQUITO resistance to insecticides made from pyrethrum has now attained 99.8 percent of malaria spots monitored across the country, experts have confirmed.

Prof. Nicodem Govella, a senior researcher at the Ifakara Health Institute (IHI) and lead investigator for the study, made this assertion citing findings of the study published last week in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

The researcher who has for years been linked with the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine said in the study summary that the development that threatens to reverse years of hard-won progress against malaria.

The study has confirmed a growing and dangerous challenge to public health in Tanzania, as mosquitoes are becoming increasingly resistant to pyrethroids, the primary range of insecticide brands used in treated bed nets.

An online description says that most anti-mosquito sprays similarly use synthetic compounds called pyrethroids, which are derived from natural pyrethrins and are effective at killing insects. Common examples include permethrin, bifenthrin and deltamethrin. While effective, pyrethroids are broad-spectrum insecticides that also harm beneficial insects like bees and butterflies, the rapid description noted.

The study findings suggest that for more than two decades, insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor spraying have been central to the malaria control strategy, helping to prevent millions of cases globally.

However, the study, found that the effectiveness of pyrethroids is rapidly diminishing, explaining that an insecticide is considered highly effective if it kills 98 percent of mosquitoes upon exposure.

Mosquito mortality rates below 90 percent signal fairly strong resistance, and with pyrethroid spraying mosquito mortality now below this threshold in most areas, mosquitoes are living long enough to transmit malaria parasites, rendering bed nets and sprays less protective.

"This is dangerous. Areas where malaria cases had dropped are now seeing a resurgence,” the researcher noted, while the findings show that other efforts are being pursued to cover the gap of the diminishing efficacy of traditional pyrethroids.

The study, which analyzed national data from 2012 to 2021, confirmed that other insecticide classes, including carbamates, organophosphates, and organochlorines, remain largely effective. Resistance to these alternatives was recorded in only 7.4 percent, 0.2percent and 1.3percent of areas monitored in the study.

“This is a strong signal that we can still control malaria if we shift our strategies wisely,” the researcher said in other remarks, while the report calls for an urgent transition to next-generation nets and alternative insecticides that combine different chemicals to outsmart resistant mosquitoes. It also emphasizes the importance of community-based prevention, such as clearing stagnant water where mosquitoes breed.

The research was a collaborative effort involving IHI, RTI International, the National Malaria Control Programme, the Zanzibar Malaria Elimination Programme and international partners.

The researcher’s message is one of cautious optimism. "Every parent hoping their child sleeps safely under a net, every health worker on the frontline—this research gives them hope. We see the challenge. We have alternatives. We can still win the fight against malaria,’ he declared.

Top Headlines

© 2025 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED