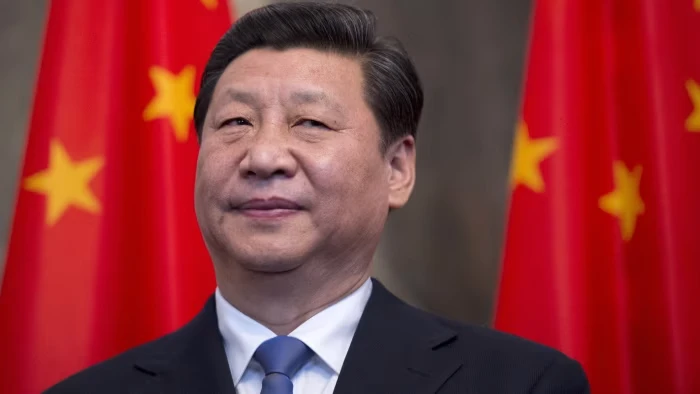

Reflection and Purpose: Wang Yi’s visit signals China’s growing sway in Tanzania’s foreign policy

In January 2026, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi began his journey in Africa by visiting Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and then going to Somalia, Lesoto and Tanzania.

I don't know how others might see through it, but in my view, this schedule is more than just a sign. It reflects a well-planned, comprehensive approach to Africa, grounded in mutual respect, continuity, and the keeping of promises made by the highest levels of government.

Having examined the mutual relationship put forward by the Chinese government in some of my previous articles, this time I examined the strategic constraints China faced before Wang Yi's trip to Africa in 2026 from a bird’s-eye view.

From an economic perspective, these geopolitical, economic, and institutional challenges could shed light on, and importantly, help us understand why Africa is more important to Beijing than ever before. As I will cover in the next article, I will explain what lies beneath this to understand what China wants to do on the continent at this point in history.

Wang Yi's annual trip to Africa at the beginning of this year is, in my view, not only a courtesy visit but also a well-planned diplomatic mission to strengthen China's standing in the world amid evolving global uncertainty and strategic competition. It is important for those who might have forgotten to remember that Wang Yi's January 2025 trip to Namibia, the Republic of Congo, Chad, and Nigeria preceded the 2026 visit.

Much as it might not be obvious, that earlier tour was planned, not an accident. Namibia, a SADC member state, showed that China was increasingly interested in key minerals crucial to the shift to green energy.

The Republic of Congo, also an SADC member, showed how long-standing energy and infrastructure connections are in Central Africa. At a time when the region was unstable and the world was changing, Chad announced it would re-engage strategically with the Sahel.

Likewise, Nigeria, Africa's most populous and economically powerful country, confirmed its role as a key partner for China in West Africa and across the continent.

The 2025 tour showed that Beijing prefers geographic balance, resource security, political power, and working with Africa's most important regional anchors. More crucially, it showed that China's Africa-first diplomacy is not merely a passing fad or a symbol; it is a strategy that is examined, changed, and updated every year.

I am not quite certain about other analysts’ views on how beneficial China is in supporting emerging nations in standing up, but generally, understanding this background is necessary to make sense of Wang Yi's visit in January 2026.

Those who have studied history would agree with me that China's approach towards Africa has evolved through different stages. In the years immediately after the Cold War, political unity and diplomatic survival were paramount.

In the 2000s, there was extensive cooperation on resources and infrastructure financing. The Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) strengthened the relationship in the 2010s.

By 2026, Beijing had entered a new phase of strategic consolidation. The focus is, in my view, no longer on expanding its footprint at any cost. Instead, it is about stabilising ties, preserving investments, securing supply chains and markets, and ensuring that African collaborations align with China's broader global strategy for mutual benefit. The purpose of Wang Yi's visit is to do exactly these things.

This recalibration is occurring at a time of rapid change in global politics, particularly amid trade tariffs and other engagements, some justified and others that completely circumvent internal law. When one critically examines what is happening around the world right now, the unquestionable conclusion is that the world system is unstable, and that nations and administrations, such as Beijing, are learning from these events strategically.

So, one of China's short-term goals is to reassure other countries through diplomacy. Africa is still a stabilising force and anchor in world affairs. African governments have significant influence over the rules and procedures of the United Nations because they are the largest and most unified voting bloc. Unquestionably, Beijing is aware of this.

China is under more scrutiny than ever for how it acts around the world, so it's more important than ever for Africans to comprehend or at least stay impartial.

Thus, in my assessment, Wang Yi's visit strengthens three main points. First, that China cares about African voices in world politics. Second, that Beijing wants the same to happen in multilateral forums. Third, that the Global South remains an important part of China's diplomatic identity.

From an economic point of view, this is not transactional diplomacy in the strictest sense; it is about maintaining long-term relationships on a global scale.

In fact, in the bigger picture, China is also quietly changing how it does business with Africa. The time of megaprojects that are funded by debt is coming to an end.

Now, a more selective strategy is being pursued that focuses on trade growth, market access, industrial parks, manufacturing hubs, agricultural value chains, and logistics corridors, which, in turn, have a huge impact on job creation for host nations.

For my assessment, there are two reasons why Africa is important here. It gives Chinese companies a place to relocate or diversify production due to tariffs and geopolitical risk, and it gives them access to new markets as Western economies make it harder to do business.

Because of this, Wang Yi's visit is expected to focus on ensuring that agreed-upon outcomes are carried out, making trade easier, and getting the private sector to work together rather than making big loan announcements.

But looking at the whole picture from an economic security perspective, the global energy shift is a major reason why China is paying more attention to Africa again.

Lithium, cobalt, copper, manganese, and rare earths are found across Africa and are very important to China's plans for electric vehicles, batteries, and renewable technologies.

At the same time, African governments are becoming less willing to let raw materials be mined in this way. They want processing to happen locally, talents to be shared, and value to be added. Wang Yi's job is partly to close this gap by convincing African partners that China is prepared to change while also ensuring China has long-term access to the resources it needs for its economic future.

Debt remains the most sensitive topic in China–Africa relations, particularly regarding investments and loans. Beijing knows that people around the world are questioning its status as a development partner. The January trip was, in my view, a chance to show that China is open to changing the terms of debt restructuring and rescheduling.

It also lets the onlookers change the story about debt-trap diplomacy and show that China is part of the solution to Africa's financial problems. This is as much about trust as it is about money.

Lastly, Wang Yi's trip to Africa focused on security and the story. China's actual presence on the continent, as shown by its people, businesses, infrastructure, and trade routes, has grown significantly. Political unrest in parts of the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and the Gulf of Guinea is now directly affecting Chinese interests.

However, Beijing remains cautious about direct involvement in military operations. It prefers diplomacy, development, and cooperation with other countries, an approach that makes China unique when compared to others.

Africa is both a place where China can test its limited security posture and a place where it can strengthen its narrative of sovereignty, non-alignment, development, and South-South cooperation in a world moving towards bloc politics. Wang Yi's trip in January 2026 is not driven by sentiment or routine. It is a mission with several layers, including diplomatic, economic, reputational, and strategic consolidation.

The visit gives Africa both a chance and a duty. It gives Africa the chance to negotiate clearer priorities and better outcomes, and it gives Africa the duty to work with China as a partner, not a patron, ensuring that China's interests align with Africa's long-term development goals.

Top Headlines

© 2026 IPPMEDIA.COM. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED